Scomi Group: From survival to success

Having divested major assets to tackle the financial strain brought about by its rapid expansion, Scomi Group is now ready for the second wind.

By JAGDEV SINGH SIDHU, The Star

IF there’s one company on Bursa Malaysia that has shed its skin many times over and morphed from one big thing to another over the years, it’s Scomi Group.

When the founders of the company took over Subang Commercial Omnibus & Motor Industries, the main motivation for the acquisition was the coach building business.

But soon after, they realised that its true potential actually stemmed from a little side business: drilling fluids (which lubricate drill bits that dig through the earth in search of crude oil and gas).

Eventually, the drilling fluids business became a major growth driver for the group, which led to its listing on the then second board of Bursa Malaysia.

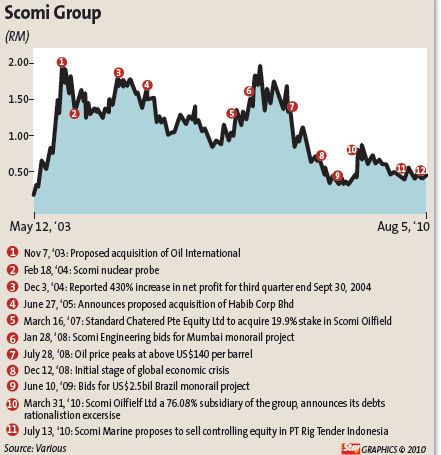

The timing of Scomi’s flotation in 2003 was spot on. Worldwide, oil and gas stocks were on their ascendency, owing to skyrocketing crude oil prices. Back home, Scomi and many of its peers rode on that wave.

“Those who bought into the oil and gas hype made lots of money. This was the ten-bagger people were looking for,” says an analyst who used to track oil and gas stocks.

Scomi’s appetite for acquisitions continued to grow. In 2004, it bought a 71% stake in Oiltools International Ltd to expand its oil and gas business.

Not long after that it took over jewellery company Habib Corp Bhd, which would later become Scomi Marine, and it entered into a RM1.3bil deal to buy vessels from Chuan Hup and stakes in CH Offshore Ltd and PT Rig Tenders Indonesia.

Its next big move was to inject its engineering division into the listed shell of Bell & Order Bhd which later became Scomi Engineering in 2006.

In 2007, Scomi Engineering bought Mtrans, a bus and monorail operator, for RM25mil and this business became the springboard from which the group would venture abroad in a big way.

But the aggressive expansion plans put a strain on the company. Disappointment set in for those who invested in the stock for its high growth potential.

The group’s earnings missed the street estimates. “Going global proved to be a major challenge,” says the analyst.

Says an observer: “There is uncertainty in the global market. A lot of people look at the company and say Scomi has a worldwide exposure, but what they may want is a Malaysia exposure.”

Perils of political links

Scomi’s major shareholder is Datuk Kamaluddin Abdullah, son of former prime minister Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi. Part of the hype surrounding the stock’s rally earlier was very much related to that – rightly or wrongly.

The pitfall of being politically linked is that when there’s a regime change, there lies a perception that the company, which had previously enjoyed certain privileges and contracts, may no longer have that luxury.

“The company is clouded by a few things… politics, US sanction issues (on chief executive Shah Hakim Zain) and so forth that no one has noticed the company’s transformation,” says a source close to the company.

In the past, the company’s officials, more specifically Shah Hakim, had denied the company had been a beneficiary of such patronage, highlighting that the bulk, or 85%, of its revenue came from outside Malaysia.

Shah Hakim and Kamaluddin have a majority stake in Scomi through Kaspadu Sdn Bhd and Onstream Marine Sdn Bhd. Both these vehicles own 15% interest in the company and together with friendly parties, the effective stake is estimated at about 30%.

Interestingly, in recent months Kaspadu is believed to have been trimming its stake in Scomi, presumably at the behest of Kamaluddin.

That has set tongues wagging that he may be looking to exit the company, given the changing times and because the company could be finding it relatively tough to secure contracts locally.

But those close to him deny such talk. “If there are contracts worth fighting for (locally), Scomi would bid for them,” says a source, adding that Kamaluddin could be partially cashing out to pursue business opportunities elsewhere.

“Scomi continues to get jobs in Malaysia but it deliberately stayed quiet on the local front to avoid fanning speculation or creating more perception issues due to the change of leadership in the country,” says the source.

Coming out of the woods

Since then, however, much has changed. After staying in its cocoon for months, it was ready to come out early this year, this time, armed with a rebranding plan largely necessitated by the global downturn in 2008.

The global financial crisis had badly hit the company, which had aggressively expanded abroad. The debts it took to fund the expansion weighed down the company and the cashflow from its existing businesses, especially its oil and gas division, fell short of earlier estimates.

To pare down its debts, Scomi divested some of its assets, including Oiltools, while it undertook a massive housekeeping of its finances. As a result, the source says, the company had cut costs by US$25mil a year.

In April this year, Scomi Marine completed the sale of a 29.07% stake in Singapore-listed CH Offshore Ltd for S$143.5mil, making a gain of RM161.9mil. In May, Scomi sold its machine shop business to Sumitomo Corp for RM327.7mil. That was not all.

In July, Scomi Marine announced its plan to sell a majority stake in PT Rig Tenders and other assets to an Indonesian fund for RM550mil.

Scomi Marine managed to cut debts from US$170mil to US$50mil and with the sale of CH Offshore and PT Rig Tenders, it will be able to emerge with a clean slate and RM600mil in cash.

At the group level, it has debt papers of RM250mil and its oilfield division has debts of some US$100mil. The target is to bring down the debts of the group and the oilfield division to RM400mil.

“There is a progressive approach to reducing the debt,” says the source. These divestments, points out the source, were not done at fire-sale prices.

“Scomi bought the machine shop business for US$10mil and sold it for US$110mil. It sold the marine business for 60% more than the price it paid,” he says.

Forging ahead

Scomi is now in the midst of a three-year programme that runs till 2011. The target is for the businesses within the group to generate a return on capital employed (ROCE) of 25%. To this end, the company has scrutinised its profits, cashflow and balance sheet management.

Having done so, it has identified the companies or businesses within the stable that have no chance of meeting the ROCE target by 2011. The outcome – it sold its machine shop which was facing margin pressures.

Similarly for the marine business the price of vessels at one point was so high that it was pointless to buy new vessels as it would not have met the internal rate of return of 15%.

Now that the price has come off, Scomi Marine, with its cash hoard, is trawling for new purchases after relinquishing control of its Indonesian marine logistics business.

The source says the company is confident it can hit 22% ROCE by 2011 and if more problematic assets are sold, the group’s ROCE could inch closer to 25%.

One example is its oil and gas operations in Venezuela, where inflation has hit the roof. Scomi stands to be penalised under International Financial Reporting Standards and would have to take a huge charge for that. Needless to say, selling off the operations in Venezuela would raise more cash and help improve its balance sheet.

Prospects of monorail

While oil and gas, which is expected to contribute 40% to group revenue, continues to be its pillar, it’s the monorail business that’s getting the company really excited, given the enormous potential of urban transportation globally and more so, in three of its target markets – India, Brazil and Indonesia.

The group’s major breakthrough in the global monorail space came when Scomi Engineering won a RM1.84bil bid in 2008 to build a monorail project in Mumbai with its Indian partner Larsen & Toubro. Its share of that job is RM823mil and projected margins are between 10% and 20%.

The Mumbai project has since been its launch pad to compete on an international scale to grab more jobs. Once the job is completed some time mid next year, and apart from the KL Monorail, it’ll have the Mumbai monorail to further sweeten its track record.

India is a difficult market to crack for international companies but given its involvement in Mumbai, sources say the company has been approached for monorail projects in other Indian cities.

In Mumbai, there are another 184km of monorail lines that are scheduled to be built over the next three to four years. Pune is coming up with its own monorail, and Bangalore and Chennai are the other cities targeted by the company to roll out a monorail line.

“The company is also in discussions with other cities. People want to see how well Scomi does in Mumbai (first),” says the source.

In Brazil, it is reported that Scomi Engineering is re-tendering for a job worth some RM3bil in Sao Paulo. Prior to this, Scomi Engineering was asked to come up with a proposal for a monorail that can carry an identical number of passengers as an MRT.

Typically, monorails carry fewer passengers than a LRT or MRT. After extensive research and development, Scomi came up with the newest-generation monorail with an eight-car configuration, versus the current four-car configuration for the monorail in Mumbai. This monorail can carry 1,000 passengers, the same as a six-car LRT.

Jobs at home

While it pursues jobs abroad, the source says Scomi Engineering is not forsaking its prospects in Malaysia.

It is in negotiations with Syarikat Prasarana Negara Bhd for a RM600mil job to upgrade the monorail in KL to a four-car configuration and is refurbishing wagons for KTM Bhd. There are also talks on a Putrajaya monorail and another in Johor.

Scomi Engineering ploughs back some 20% of its revenue into research and development on trains to build more efficient monorails. The next-generation monorails it is building is called Gen 3.0 and would be the size of a LRT wagon.

It is also evaluating the prospect of going into trains, where it can build LRTs or EMU (electrical multiple units), which is the kind of trains KTM uses for commuter service.

“There is a plan to transform the organisation on the drawing board,” says the source.

Currently, it is awaiting more clarity on the proposed MRT project for KL before it decides to submit its own proposal for the city’s transportation needs.

“You have to look at cost per passenger, cost-effective solutions. Do we really need to spend RM50bil on a MRT?” he asks.

Scomi Engineering also has a bus-building business which caters more to the high-end market. It builds about 250 buses a month and it exports luxury coaches to Hong Kong monthly to a long-standing customer there.

Fending off competition

The monorail business globally, however, is not without its challenges. For one, it’s highly competitive. At the moment, Scomi Engineering’s competitors include Hitachi, Bombardier and a few upstarts from China and Russia.

What’s its edge? “Technology evolution is important for Scomi along with its track record and execution,” says the source.

The source claims that Scomi has a cost advantage compared with Hitachi and Bombardier as it strives to continuously reduce its price to ensure that its monorails are more cost effective.

He also claims that the company can build a system in 24 months, faster than its main rivals. After establishing ties in India and Brazil, and hopefully in Indonesia soon, the company may look at the secondary markets such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, Turkey, Sri Lanka, Egypt, Iraq and Nigeria – internally called the G-8 countries. These countries have large populations and are in need of upgrades in public transportation.

“This will be more apparent in the company’s 2012–2014 strategy,” says the source. “What a company needs to do is when it enters a country, it has to be as comfortable with the country as it is with Malaysia. Otherwise, it will be second guessing stuff,” says the source.

Like in India and Brazil, Scomi will seek to establish ties with a large and established partner in those countries as a means of mitigating risks.

The marine business

Changes in the cabotage laws precipitated the sale of its marine logistics business in Indonesia. Stricter enforcement of such laws is expected elsewhere and for the company to grow, it has to figure out a way to deal with the stricter implementation of the laws.

One of Scomi’s strengths in the marine business is its international network. In Indonesia, its marine business rakes in a revenue of US$180mil. To be big in shipping in Indonesia, Scomi needs to tie up with a coal player.

It’s now looking at ways to leverage on its coal business in India as it feels there is a growing demand for coal to fire up the country’s power plants.

The source says Scomi Marine can fill the gap in India, which does not have big shipping companies like China.

India has two large shipping players. The market in coastal and international shipping is enormous and the country is building a number of ports along its coast.

To bypass the cabotage issues in India, Scomi Marine would need to find a partner in India.

“Build it like Indonesia so that India and Indonesia will be the sub-market with Malaysia in the centre,” says an observer.

The concept Scomi Marine is looking to adopt is akin to that employed by AirAsia. “AirAsia has domestic partners in countries it operates in like Thailand and Indonesia. But the Malaysian fleet goes everywhere. That’s what it wants to do,” says the source.

Scomi needs to complete the sale in Indonesia before it can start that phase of its business plan under its 2012–2014 programme. The sale in Indonesia would give the company a boatload of cash. So, what will it do with all that money?

“At the moment, the only certainty is that there is a need to re-invest the money so that more revenue and profit can be generated to maintain the listed status of Scomi Marine,” he says.

“It would be looking at re-investing in vessels as prices have dropped. This is the right time to do that.”

Furthermore, Scomi Marine’s Indonesian partner wants to invest in panamax for long haul and Scomi Marine might start exploring the long-haul opportunities of shipping coal.

Slippery slope

The drop in global rig activity during the 2008 worldwide recession hit Scomi hard and although a lot of the markets that Scomi is in are doing well, it is struggling in a few others.

Scomi Oiltools’ drilling fluids operations in Aberdeen have suffered as the level of activity in the North Sea has dropped and it is also being hurt by the high cost of operations there. The other headache is Venezuela.

The market in the United States was also a drag on the group, but the source says things are “slowly coming back.”

“After dropping from 2,000 to 800 rigs, that market is now back up to over 1,000 rigs but as volumes have dropped, so have prices. Margins are squeezed in the US,” he says.

Operations in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Nigeria are doing well. The next country on the cross hair of Scomi Oiltools is Iraq.

“The oilfield business is big there and Scomi is bidding for a lot of work there. Apart from the oil and gas business opportunities, Scomi thinks public transport is the next huge area for the group as there are a few monorail projects coming up,” says the source.

The next phase

The company aims to become a Malaysian multinational and to drive this aspiration forward, it is keen to nurture the next generation of top executives.

Its monorail business in India and Brazil, along with the prospects in the marine business for the longer ferrying of coal, would change the dynamics of the company, which has in the past laid its hat on the oil and gas industry.

In Malaysia, contrary to perception, the company insists that it’s business as usual. “Scomi is associated with energy and logistics. The focus is the same but the profiling is in public transport,” says the source.