A second chance for bankrupts

Malaysia has one of the most stringent bankruptcy laws in the world, but a review may be in the offing.

According to the Malaysia Department of Insolvency, between 2005 and June 2012, a total of 243,823 people have been declared bankrupt in the country.

Shahanaaz Habib, The Star

SAM, an engineer, met Ling when they were both studying in college. They dated for years and even made plans to get married.

When Ling bought a car, Sam stood as her guarantor. But Ling did not pay her monthly instalment and Sam ended up paying it for her. Then one day, to his horror, Sam found out that Ling was in fact engaged to someone else.

Heartbroken, he broke off all contact with her, changed jobs and moved to another state to get over her. But Ling continued her habit of not servicing her car loan till the bank finally repossessed her car and auctioned it off. Even then, there was still a shortfall of RM45,000.

Since Sam was the loan guarantor, the bank went after him to recover the outstanding balance and started legal proceedings against him. If he did not settle the amount, he would become a bankrupt.

Office executive Nadira is just 28 but she may find herself on the road to bankruptcy unless she changes her lifestyle.

Nadira, who has two credit cards, loves to hang out at cool places in Bangsar and spend holidays locally and abroad with her friends. She also enjoys dressing up and splurging on new clothes, shoes and make-up. She shares an apartment with two friends and has an LCD TV in her bedroom. She drives a Viva and owns the latest iPad and Blackberry.

Nadira took out a RM26,000 student loan for college but hasn’t repaid a single sen because, she says, her RM3,400 monthly salary is not enough to cover her monthly expenses, which include car loan instalment, petrol, rent and living costs. Over the years, the unpaid student loan plus interest has ballooned to RM42,000.

Her credit card debts, too, have been mounting up as she doesn’t pay the full amount at the end of the month, thereby incurring exorbitant interest and finance charges.

Nadira may not realise it yet but it doesn’t take much for a person to be declared a bankrupt in Malaysia.

If the borrower or the guarantor (who is equally liable) has a debt of RM30,000 or more and has not been repaying that loan, the financial institution or creditor can institute bankruptcy proceedings to get their money back.

And it is tough being a bankrupt. When a person is declared a bankrupt, their existing bank accounts will be deactivated. This means they cannot withdraw money, open a new account or use their existing account unless they get permission from the Director-General of Insolvency (DGI). Their assets will be frozen and sold off to pay the debtors; they are unable to get new loans or travel overseas (unless they get written permission from the DGI) and can only use a credit of up to RM1,000 on an existing credit card. Their standing in society is damaged and they can forget about any political ambitions as they would not be allowed to stand for elections.

According to Rembau MP and Umno Youth chief Khairy Jamaluddin, who has been pushing for a review of the Bankruptcy Law to give people a second chance, Malaysia has one of the most stringent bankruptcy laws in the world.

“A creditor can file for bankruptcy for loans above RM30,000. It is not millions. And once a person is declared a bankrupt, it is very difficult for him or her to start life again.

“Bankrupts cannot take out loans or start a business. They have to wait years to be discharged from bankruptcy and that process is quite onerous,” he says.

Statistics reveal that 51% of bankrupts in Malaysia are people below 45, a phenomenon that Khairy finds “very alarming”.

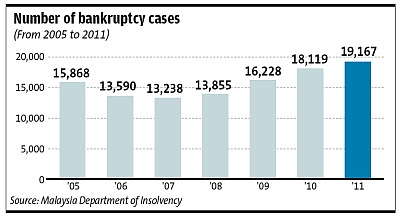

According to the Malaysia Department of Insolvency, between 2005 and June 2012, a total of 243,823 people have been declared bankrupt in the country.

“The statistics keep going up. About 52 people are declared bankrupt every day now compared with 36 in 2007.

“If you look at the breakdown, about 16% are (due to non-payment of) business loans, the rest are housing, personal, or car loans. About 25% go bankrupt because of car loans.

“You have to address the problem at the source banks are giving out loans too easily. There should be better regulations where car and other loans are concerned,” says Khairy, who is Perbadanan Usahawan Nasional Berhad (PUNB) chairman.

Khairy says PUNB has just approved a loan to a motorcycle dealer who informed them that sales of super bikes have skyrocketed in the country because banks are making it easier for people to get loans to buy these high-end luxury motorcycles.

“These are impulse buys and my concern is that when people are faced with easy credit, they tend to live beyond their means.

Tempting promotions: The public is inundated with offers and discounts, with companies spending millions on advertising to get people to buy. — AFP

Tempting promotions: The public is inundated with offers and discounts, with companies spending millions on advertising to get people to buy. — AFP “This whole business of personal debt could be a potential time bomb if we don’t intervene now,” he says, noting that Bank Negara has rightly imposed stricter restrictions and limits on credit cards but feels that more should be done to rein in easy access to loans.

Fomca deputy president Muhammad Sha’ani Abdullah, who agrees that the bankruptcy law should be reviewed, says that when financial institutions approve loans, they should also be responsible for assisting a borrower who is facing financial difficulty.

“Banks should not use their dominant position to victimise their customers,” he adds.

But he stresses that wilful delinquent borrowers should be penalised accordingly.

In genuine cases, he says, there should be a provision in the bankruptcy law where financial institutions have to prove that they made a serious effort to assist the borrower before initiating bankruptcy proceedings.

He says banks should also look into the background of the borrowers who default on their loans.

Some get into financial difficulty because they have to foot high medical bills as a result of critical illness or are accident victims or retrenched workers who have lost their livelihood.

There are also cases where housebuyers who have obtained loans are left in the lurch when the project is abandoned. Even if these housebuyers form a buyers’ committee to try and revive the project, Sha’ani says, they often face non cooperation from the financial institutions because the contract terms in the sale and purchase agreement give them a disproportionate advantage to demand their loans.

“There should be a new law or an amendment to the Consumer Protection Act 1998 against unfair contract terms in agreements,” he adds.

He also questions why legal action is taken against guarantors when the principal borrower is easily identified and financially able.

Calls to review the country’s bankruptcy law are not new. In the past, the government has said it would look into the possibility of an automatic discharge after a certain period of time, which is the norm in most countries. Currently, the law does not allow an automatic discharge.

Thus, a bankrupt can only be released of his bankruptcy status after applying to the court for the bankruptcy order to be annulled on grounds that the debt has been settled, or apply for a discharge which would be subject to stringent requirements and with the Insolvency Department putting in a report emphasising the conduct and cooperation of the bankrupt with the department.

After five years of bankruptcy, the person can also apply to the DGI for a discharge under section 33A of the Bankruptcy Act 1967, which is subject to the DGI’s discretion.

Khairy says one of the things they are asking for is an automatic discharge of a bankrupt.

He points out that in Australia, a bankrupt is automatically discharged after three years if there are no objections. In the United Kingdom, it is a year but the bankrupt still has to pay his student loan and alimony (which are non-dischargeable loans), in Canada it is nine months for the first bankruptcy, and in Thailand it is three years as long as the bankrupt is not involved in fraud.

“In Malaysia, it is a minimum of five years and that is at the discretion of the DGI. It is difficult. Not everyone can settle all their debts. And people want to move on. I don’t think we should punish them forever. So we would like a timeline for an automatic discharge. Two to three years is ample,” he says, adding that bankrupts should be given a second chance to re-build their lives.

But he stresses that it is not a second chance to be a spendthrift and there has to be a balancing act between lifting the life sentence of bankrupts and not wanting to create a spendthrift bankrupt culture.

He points out that some people become bankrupt because of unexpected incidents like a flood or downturn.

There are also cases where a good business idea did not quite take off due to weaknesses in execution and implementation. He says that in innovation, nine out of 10 businesses fail.

“If you send out a message to people that if you fail you are screwed up forever, it is not an incentive for them to go out there and try. We don’t have enough entrepreneurs and SMEs in this country.

“And you don’t want this to be a death sentence, like a guillotine over their heads.

“You want to make sure they get a second chance as long as they still have the idea and the drive. The moment people are scared of taking risks, of taking business loans, of starting a business (because they fear the stringent bankruptcy laws), it is a disincentive.”

There are many who became bankrupts because they were guarantors for someone else’s loan. Khairy says people should be very careful and do their homework before agreeing to be a guarantor.

He also fears that if the law is not amended to give bankrupts a second chance, then these people might end up turning to Ah Longs to borrow money and end up in deeper financial trouble because they cannot get loans from the legitimate financial institutions.

Khairy does not believe that an automatic discharge would be an incentive for young people to get into debt, become bankrupt and then wait out the two- to three-year period to be automatically discharged from bankruptcy.

In any case, he says, even if a person has been discharged as a bankrupt, this will remain on his financial record. Financial institutions know this and will weigh the risk before giving him another loan.

“We will not disqualify a former bankrupt if he applies for a loan because the purpose is to allow him a second chance. But we will want to know why he became a bankrupt and whether it was because of mismanagement.”

Khairy also says the public is inundated with offers and discounts, with companies spending millions on advertising to get people to buy. In comparison, the government and consumer groups are not spending as much to create awareness on personal financial management.

“The whole world is geared towards consumption. Our concern is consumption based on credit. Young people out of university have student loans to pay off, they want to get married, take a housing loan and a car loan.

“We need to educate people from young that they have to live within their means. And when they take out a loan, they have to project their income over the next five to 10 years and be realistic about it,” he adds.

When PUNB goes through loan applications, they will ask for details on the person’s business debt exposure and personal debt as well.

“Sometimes an entrepreneur’s business is doing okay but his personal finances are not. We look at the houses he is buying or the type of cars he is driving. If his salary is not going to meet the monthly payment for the loans and I don’t want him to start embezzling from the firm to pay for it we will reject the applications.

“We want to make sure that when a loan is given out, the money comes back to us.”

The Insolvency Department say they are looking at all issues as the insolvency policy should not stand alone because it has an impact on other government policies.

As such, a holistic approach and comprehensive study is required to ensure effective implementation, they state in their e-mail response.