“Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains”

If I were to lead Malaysia the first step I would take into restoring sanity in the country would be to outlaw ALL religions. Then part of the country’s problems would be solved. But then would 90% of Malaysians who believe in the unseen and unproven God agree to that? Would that not be the tyranny of the minority over the majority?

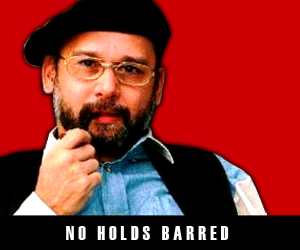

NO HOLDS BARRED

Raja Petra Kamarudin

I thought I would share the following article by Guy Dammann published in The Guardian about two years ago (see below). If you want to know more regarding the subject then I would suggest you read ‘An Introduction to Political Philosophy’ by Jonathan Wolff (Oxford University Press).

The reason I am writing this article is because of the many comments posted in Malaysia Today about the grouses of the non-Malays regarding what they regard as unfair treatment, injustices, racial discrimination, lack of meritocracy, and much more.

I have, in fact, written about this same matter earlier but it looks like the message I am trying to deliver has not gone through. This normally happens when you speak to those who have a mental block and have already formed a certain opinion even before they read what you have to say.

And I certainly do not blame these people just as I do not blame the non-Malays for feeling that they are being given a raw deal. I would certainly feel the same way if I were in their situation. The focus of our discussion today, however, is why is this happening and what can we do about it?

And herein lies the problem. And Rousseau explains it as “Man is born free and everywhere he is in chains.”

As I have said before, democracy is not the perfect system. At best it is the lesser of the so many other evils. And, as even the non-Malays have said many times, in the absence of perfection, they would go for the lesser of the evils.

And this is the danger with accepting the lesser of the evils, as propagated by the non-Malays, and, to be honest, many Malays as well. When you accept the lesser of the evils you need to make certain compromises. And it is these compromises that are the devil in the whole thing.

In that book I mentioned above, it analyses the ideas and thoughts of Plato, Rousseau and John Stuart Mill, plus the Social Contract. Basically, these people are all of the opinion that democracy is flawed and it is quite impossible to find equality and fairness in such a system.

If I want to write about this matter in greater detail I may need to write a 20-page thesis, which most of you would not bother to read anyway. So let me try to explain this issue in the briefest possible manner.

The argument starts with the question of do we even need a government in the first place, and would society not work better if humankind is allowed to manage its own affairs rather than mandate that to a government, which means your rights have been abrogated and someone else takes over in determining your future and welfare?

Now, this has been a 2,500-year old debate and so far the philosophers through the ages have not been able to come to a consensus on the answer.

In the end, most philosophers come to the conclusion that having a government may be better than having no government mainly because of the nature of humankind where the strong will dominate and exploit the weak. Hence the weak will not find happiness or be given protection in a natural state of no government or what is called a system of anarchy.

Hence, in arguing so, the philosophers have identified the role of governments: to bring us happiness and to offer us protection. And, to be able to achieve this, we need a system where laws can be formulated and enforced with a judicial system that can punish the violators of these laws.

So now most philosophers have agreed that having a government is better than having no government. Governments may not be good but it is still the better option compared to survival of the fittest where the weak would suffer.

The next issue would be: what type of government should we have? Some philosophers like Plato say that the best system would be the benevolent dictator, one man who decides what is good for us. But what happens when we get a malevolent dictator instead, because humankind tends to exploit the weak? How then would we remove this dictator?

So the dictator idea is rejected and instead we opt for a democracy, which means the people decide how they want to be ruled and what government they should have.

Once we agree that this is the system we want, we then need to decide how we choose this government of the people, for the people and by the people. And the option we choose is through democratic elections.

But democratic elections are also not perfect because then we are talking about the will of the majority. And the will of the majority may not always work in favour of the minority. So how would the minority be protected?

And when we talk about ‘majority’ and ‘minority’ how do we determine this?

Some philosophers say we need a direct participation type of democracy and others say it should be an indirect representative type of democracy. In a direct democracy, all the people vote on a certain issue (such as we would in a referendum). In an indirect democracy, all the people just vote for their representatives (senate, congress, assembly, parliament, etc.) and these representatives vote on our behalf.

But both are still not perfect because most people would vote based on their own personal interests (or their own community’s interests) and not based on common or universal interests. Hence there would still be inequality and injustice, whichever system we adopt.

So, in analysing the flaws and weaknesses in the Malaysian example, to put the blame squarely on the political party in power would be incorrect. The fruit of a poisonous tree would be poisonous. Hence the end product of a corrupt system would also be corrupted. And democracy is not perfect so what we see in Malaysia is certainly far from perfect.

The danger here would be when politicians lead us to believe that the system itself is not flawed but only those who manipulate the system are. Hence, they say, we do not need to look at the system but just change the leadership. Then the system would work.

This is the utopian way of looking at things. The utopian system has not yet been invented. Hence, to tell the people that it does exist would be a serious misrepresentation of the truth. Democracy is flawed. Whatever you do you can never make a flawed system un-flawed.

So politicians need to be honest with the people. They should not tell the people that democracy would definitely work if we can only kick out Barisan Nasional and replace it with Pakatan Rakyat. That is utopian. And the definition of utopian is ‘excellent or ideal but impracticable’.

As long as we apply western-style democracy we will always have one community losing out and another community gaining. And if we reverse that then the gainers would lose out while the losers would gain. It cannot be any other way.

For example, say Malaysia practices a system of meritocracy. Then the qualified or deserving would get ahead while the unqualified or undeserving would be left behind. That, of course, would be fair to the qualified/deserving. But then the unqualified/undeserving would consider that unfair and they would rise up in protest. So we would still not see peace in Malaysia.

Running a government is not easy. Humankind is not born equal. And we are also not born free, as we think we are. Hence governments will never treat us equal or allow us freedom. And democracy will always be the tyranny of the majority over the minority.

That is the reality of life. And if you think otherwise then you are not a realistic person. So, you may ask, do I have a solution? If I did I would have run for public office a long, long time ago. I do not and that is why I would rather be a political observer cum commenter than a politician.

If I were to lead Malaysia the first step I would take into restoring sanity in the country would be to outlaw ALL religions. Then part of the country’s problems would be solved. But then would 90% of Malaysians who believe in the unseen and unproven God agree to that? Would that not be the tyranny of the minority over the majority?

Can you see what I mean? God help those who feel they are the most qualified/capable to lead Malaysia. You have a job that is humanly impossible to do.

*****************************************************

For Rousseau, man is born free, but kept free only by compassion

A fundamental tenet of Rousseau’s The Social Contract is that it is human institutions that set mankind free

Guy Dammann, The Guardian UK

Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. Say what you like about Jean-Jacques Rousseau, but he knew how to write a line. The Social Contract, the political treatise which earned its author exile from his home city of Geneva and a place in the Panthéon in Paris, may not be Rousseau’s most entertaining text, nor even his most profound one. But it is the one that did more than any other to inspire the French revolution. Sadly, it also did more than any other to justify the ensuing terror.

While its basic ideas proposed remain interesting, it has long been a point of orthodoxy that The Social Contract is politically impracticable. The principle that the only valid forms of political governance and legislation are those which completely reflect the desire of the population seems absurdly wishful in its thinking. Such uniformity of thought and feeling occurs rarely enough in a single household, let alone across the population of a nation state.

But one keeps coming back to that line at the beginning, which rattles round the reader’s head like a wizard’s pinball, clocking up points and connections. Its rhetorical force is immense. So much so, in fact, that many have questioned whether it really means anything at all.

The first time I read it, was long before I ever read The Social Contract. It was in an article by Conor Cruise O’Brien in the Heroes and Villains column at the back of the Independent’s excellent original Saturday magazine supplement, back in the 1980s.

Rousseau was O’Brien’s villain. The Social Contract‘s opening statement had no more meaning, he suggested, than the parallel idea that “all sheep are born carnivores, and everywhere they eat grass”. Man is not born free, was his argument in a nutshell, but is set free by the creation of the human institutions that protect his rights.

The funny thing about this, as I came to realise, is that Rousseau would have agreed. Not about the sheep, but about the fact that it is human institutions that set mankind free. For it is only in one sense that The Social Contract‘s famous proposition looks forward – that the chains limiting mankind’s freedom derive from non-democratic forms of governance, enacting laws which the people neither desire nor approve. But in another sense it looks back to Rousseau’s earlier Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, which Rousseau saw as being foundational to The Social Contract‘s arguments (and indeed to everything he wrote).

It is in this book that Rousseau first unveiled the subsequently much-misunderstood notion of the noble savage. This proto-Darwinian idea that modern man evolved from an animal state was of course deeply shocking to contemporary readers, but it was nothing like as shocking as the idea that savage man in the state of nature is essentially a happier and less depraved creature than the men and women of modern society.

Man in the state of nature is, like animals, equal to his desires in the sense that he does not desire things for which he has no need, or need things for which he has no desire. His consciousness of the world around him, in other words, is efficiently tailored to meeting his needs for survival and reproduction and is not enslaved by the kinds of desire in which today’s society specialises: objects and accoutrements whose value exists only in their power to make others see us in a certain light. Modern man, Rousseau argues, is the victim of a divided subjectivity, spreading disorder and unhappiness while convinced that he’s acting in his own interests.

This key here is that man in the state of nature lacks individuation and thereby any means to distinguish his individual needs from those of his community. What he does have, however, is what he calls “perfectibilité” – what Darwin would later call adaptability to change. It is through this evolutionary process that human consciousness becomes individuated, and that the sphere of human desire moves beyond what is given to him to desire.

And while it is only at this stage that it becomes proper to speak of human being in the sense (more important in Rousseau’s day even than our own) of a morally free being, it is also at precisely this same stage than man becomes depraved, identifying his own interests against and above those of his community, and perceiving desires for things he only needs for increasing his power over others.

The statement that man is born free, and is everywhere in chains, is therefore only partly about politics. On a deeper level it is a statement of a dichotomy fundamental to the idea of mankind (as distinct from the animals): that man’s enslavement is the flipside of the coin on which is stamped his basic freedom. Man is free, in other words, precisely because he becomes susceptible to enslavement. And for Rousseau, the one thing that maintains the relationship between the two sides, and prevents enslavement from taking over completely (though he might well argue that it is now too late), is a leftover from our natural state: the supreme human institution of compassion or pity.

The basic idea of The Social Contract is to construct political institutions that allow the rule of compassion to provide the basis for legislation. Although disastrous in practical politics, it is a beautiful idea to which we should pay more than lip service. The idea that we should privilege forms of interaction which develop our compassion – such as, above all for Rousseau, music – remains spot on. If nothing else, his prescience about Darwin’s theory of evolution deserves respect. Moreover, sheep are not born carnivorous, whereas man – at least while we still dare to say it – is born free.