Spotlight on Sarawak and Selangor

Constitutional issues are coming to the fore, revolving around the posts of the head of government and head of state

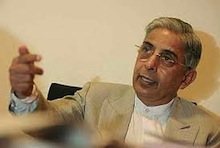

Shad Saleem Faruqi, The Star

The impending resignation of Sarawak Chief Minister Tan Sri Abdul Taib Mahmud and the gripping stories about the plot to replace Tan Sri Khalid Ibrahim as the Mentri Besar of Selangor raise interesting issues of constitutional law.

Tenure: Taib’s 33 years at the helm of the largest state in the federation highlight a rather unsavoury aspect of Westminster democracies, viz. that there is no limit to the number of terms a Prime Minister or Chief Minister may serve in office.

Antonio de Oliveira Salazar of Portugal served as Prime Minister for 36 years. Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore and Pham Van Dong of Vietnam held the reins of power for 31 years each. Hun Sen of Cambodia, Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad of Malaysia, Sir Robert Pole and William Pitt of the United Kingdom held the fort for 29, 22, 20 and 18 years, respectively.

Such lengthy tenures provide continuity of leadership but also personalise power and hinder accountability. For this reason, the US Constitution wisely limits the term of the president to two periods of four years each. In the Philippines, the president is limited to a single term of six years.

Split executive: The American and Philippines presidents are head of state as well as head of government. In contrast, in parliamentary systems there is a “split executive” – the head of the state and the head of government are different persons. This is a potential safeguard against abuse of power by the political executive. Regrettably, the system has also engendered the practice of the head of state and the head of government taking turns at each portfolio and perpetuating a dynastic hold on power.

Fidel Castro of Cuba was prime minister and then president for 52 years. Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal of Mongolia, Enver Hoxha of Albania, Paul Biya of Cameroon, Josip Tito of Yugoslavia, Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe and Habib Bourguiba of Tunisia held one and then the other post for 44, 40, 38, 36, 33 and 31 years, respectively. Now Taib is poised to join this list by ascending the Sarawak Governor’s post after occupying the Chief Minister’s portfolio for 33 long years.

Selangor: If the rumours are to be believed, the Kajang by-election is being engineered by PKR to install Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim as the new Mentri Besar of Selangor. Many constitutional crevices will have to be traversed before this plan can materialise.

Resignation: There must be a resignation by Khalid, the incumbent MB. He appears to be firmly in the saddle with 44 out of 56 seats in the assembly, the strong backing of PKR’s coalition partners (PAS and DAP) and considerable popular support. Even if he relinquishes, there is no guarantee that the Sultan of Selangor will accept his resignation mechanically. The Ruler may ask him to stay on.

Alternatively, the Sultan may ask the MB to delay his departure pending resolution of the impending criminal appeal against Anwar. The Ruler may be concerned that if Khalid is replaced with Anwar but the latter is convicted on appeal, the MB’s post will fall vacant again.

Under Article 64(1) of the Selangor Constitution, a person is disqualified from being a member of the legislative assembly if he has been convicted of an offence and sentenced to one year or more of imprisonment or fined RM2,000 or more.

Vote of no confidence: If Tan Sri Khalid resists his party’s command and does not resign, then PKR has to explore other ways to replace him. One would be to pass a vote of no confidence in him in the assembly. This is what happened to PAS Mentri Besar Datuk Mohammad Nasir in Kelantan in 1977 when his own party voted him out of office.

In such a case, the MB may not go quietly. He may advise dissolution of the assembly. Under Article 55(2)(b) of the Selangor Constitution, the Sultan has wide discretion to accept or reject this advice. If the advice for early dissolution is accepted, then under constitutional conventions, the incumbent will remain as caretaker MB pending the polls. One must also note that if the MB is voted out, all other appointed executive council members must also step down in pursuance of the principle of collective ministerial responsibility and the Sabah case of Datuk Amir Kahar v Tun Mohd Said (1995).

Dismissal by the Sultan: If the Selangor assembly is not in session, then another way to remove the MB would be for Pakatan Rakyat to convince the Sultan that the incumbent has lost “the confidence of the majority of the members of the Assembly”. Judicial precedents from Sabah and Perak have established that the question of confidence need not be determined on the assembly floor. It can be determined in other ways. In such a numbers game, the discretion of the Sultan to determine who has the requisite number of supporters is indeed very wide: Article 53(2)(a).

Suspension or expulsion: A third but extreme possibility may be to suspend or expel the MB from his party. However, this may not be fatal to his right to continue in his post. Notwithstanding what PKR thinks of him, it is the majority in the assembly in whose hands his destiny lies. In India in the late sixties, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was expelled from her Congress Party. However, as she still retained majority support in India’s lower house, she remained in office much to the chagrin of her former party colleagues.

Sultan’s discretion: Appointment and, in extreme cases, the dismissal of the MB are undoubted discretionary functions of the Sultan under Article 55(2)(a) of the Selangor Constitution. Post-2008 precedents in Perlis, Selangor, Perak and Terengganu underline this point.

It will not be surprising that in the eventuality of Khalid’s resignation or dismissal, the Sultan may not appoint the PKR nominee but may anoint a stakeholder from PAS who, in the Sultan’s opinion, can cobble together a working majority.

Obviously the vicissitudes of the law are many and in politics one can never take anything for granted.

Shad Faruqi is Emeritus Professor of Law at UiTM.