The curios case of Gopal Sri Ram

Raggie Jessy

A courtroom is a crucible. In it, we burn away all irrelevancies, until we are left with a purer product, one we could hold to be a truth for all time or until such a time, when this ‘truth’ is challenged.

Purer, considering that jurisprudence may well be confined to principles of convention relevant to an era, and limited by the proficiencies with which men of good conscience arbitrate, advocate or prosecute in litigation towards equitable resolutions. And every so often, one is guided solely by his/her moral certitude in scrutinizing otherwise indiscernible pieces of information presented as evidence.

As such, verdicts may never appear square to some. If they always did, there would cease to be reason for litigations, leaving us with fewer disputes. But it never is quite that simple. The guiding principle, as far as I understand it, has always concerned the greater good of the many, although decisions reached may not necessarily be reflective of an established moral centre.

By the same token, conventions endemic to an era may be manifestations of moral centers manipulated for the benefit of a few. The proceeding cases help exemplify circumstances where such precepts take precedence.

1. The Curious Case of British Slavery

The age of slavery simply serves to rip a chapter out of history and put in perspective not only the prevalence of skewed moral centers among a people, but the pursuance of jurisprudence to conventions.

Such were times, when blacks stood encumbered and castigated, with their rights and liberties as humans usurped. The Yorke-Talbot Slavery Opinion (1729), signed by the then Attorney General and Solicitor General of England, pretty much sanctioned slavery in a manner of an opinion. Slaves were openly traded in commodity markets at London and Liverpool, and were supplied to England’s many colonies. Disenfranchised and overworked, they had little to eat and lived deplorably. They were destitute of healthcare, contracting diseases that, although curable, grew terminal.

British atrocities were in cold blood; a slave was to be seen, and not heard. Heck, I’m doubtful that they wanted to be seen, for a whiplash may well have been the trade in retribution to minor misdemeanors. Females in their class embraced prostitution to coffer up contingencies. My gut feeling tells me, that conceptions from such atrocities were not spared. But I can’t be certain.

It wasn’t until the second half of the Georgian era that things began to change. The Evangelical English Protestant and Quaker groups began to exhort a people to detest slavery, impressing upon their faithful the need for salvation in the name of Christ. Powerful and hypnotic oration led to a deep sense of spiritual conviction among followers. Over time, a sizeable majority of Parliamentarians sought for restitution on moral grounds.

There is a lesson to be learnt here.

Conventions roll up quite a stake with jurisprudence and history. In the heyday, man could have property in another, while courtrooms still concerned themselves with the greater good of the many. That is to say, the economy flourished on the servitude of nameless and disfranchised individuals, all disposable, all property. It appeased to your average John or Smith, who was eudemonic at best, reaping the harvest of his demented sense of virtues.

The Evangelical English Protestant and Quaker groups gave rise to unequivocal paradigm shifts, liberating the parochial minds of the Englishmen, who began to embrace salvation in a biblical sense. And yet, it remained a question of the greater good of the many; a vast majority gradually sought for the emancipation of slaves in redemption.

You see, one way or the other, it has always been about the greater good of the many, against the needs of the few. And it has always remained a question of convention, as I see it.

Now that we have that established, let us get to the issue at hand.

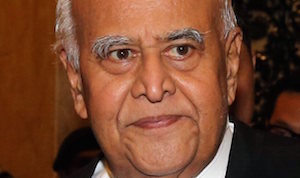

2. The Curious Case of Gopal Sri Ram

Gopal Sri Ram, a retired Federal Court judge, requested to defend embattled opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim. Contrary to what you may believe, this isn’t where I take the piss out of Anwar, or for that matter, his choice of a counsel.

No. Not just yet. This is where I begin to question some quarters that don’t seem to be guided by objectivity, simply because it’s Anwar who’s facing the brunt. Yes. A lot of us love to hate Anwar. But this goes beyond Anwar’s right to engage Gopal as his counsel; this is about the future, a precedent that would gradually result in a convention of sorts, and why Anwar would prefer engaging with precedents to these new conventions.

As far as jurisprudence goes, there isn’t reason enough to persecute or prosecute Anwar for his choice of counsel, simply because there has never been a resolution barring a retired judge from appearing as a counsel in court, in a manner that needs following through. However, one may gleefully question motives to his choice of counsel, or for that matter, motives to Gopal’s involvement. You may, because it remains your constitutional right to pose a question.

Now, it took the Evangelical English Protestant and Quaker groups to exhort a people against slavery. And they succeeded, over time, to effect restitution on moral grounds. These groups were efficacious in setting precedents towards major paradigm shifts that were soon to recalibrate right from wrong within the pillars of jurisprudence, the ones that stood subjugated by convention. In essence, these groups brought about a majority with revamped moral centers, and hence, re-established conventions that shook these pillars.

In the curious case of Gopal, Anwar has single handedly caught both the Government and the Bar Council off guard, redefining constitutions to what is permissible and what isn’t. As I’ve said, the barring of ex-judges from acting as counsels is a matter of convention that was never established definitively, in a manner that needs following through.

In the process, Anwar is redefining convention with a precedent he hoped the Government would challenge, in a manner that would have denoted vengeance or requital by a polity out to destroy him. That is to say, he wanted the Government to challenge Gopal’s appointment. Now, should that have happened, he would have been rendered a political martyr in the event of a conviction, a slave to an oppressive regime with misguided moral centers, much like the parochial English I spoke of.

Under the circumstances, he would be able to shake the pillars of jurisprudence with ‘recalibrated conventions’ arising from a ‘revamped majority’ that is ‘convinced’ of a plot to politically castrate him. With his oratory prowess, he would have blabbered on about repression and tyranny in an era where freedom of associations ought to be your birthright. And on the pretext of ‘the greater good of the many’, Anwar would have sought for his emancipation as a political prisoner, by screwing with your moral centers.

Don’t believe me?

We already have international observers, including one from the international commission of jurists, petitioning for Anwar’s acquittal, resounding precepts to ‘the greater good of the many’ in a manner of conviction, which proves my earlier stance; that conventions endemic to an era may be manifestations of moral centers manipulated for the benefit of a few.

Basically, he hopes to be rendered a political messiah, one who would ‘sacrifice his (political) life for the sins of a corrupt Government’, by going to prison. It sounds very Biblical, if you ask me. The Anwar shit will never end. Not in his head, at least.

And while we sit contemplating these issues, which are hypothetical at best, we’ve been dancing around the basic issue; what should the Government do?

Not a blessed thing.