Enhancing syariah courts’ powers

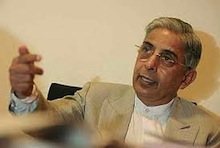

Shad Saleem Faruqi, The Star

UNDER the Syariah Courts (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act 1965, the sentencing power of the syariah courts is limited to RM5,000 fine, six lashes and three years’ jail. This power is equivalent to the power of magistrates in our civil courts.

It is understandable therefore that PAS President Datuk Seri Abdul Hadi Awang wishes for a law to enhance the status of syariah courts by increasing the penalties they can impose. However, the Private Member’s Bill he is promoting has more to it than catches the eye.

It re-ignites some critical issues of constitutional law, Islam and justice.

Criminalisation: Under the Constitution’s Schedule 9, List II item 1, state assemblies have power to enact Islamic law on 24 civil matters (like succession, marriage, divorce and Malay custom) and on one criminal matter, that is, “creation and punishment of offences by persons professing the religion of Islam against precepts of that religion”.

The power to impose criminal penalties appears to be confined to offences against the precepts of Islam. But under the “Hadi Bill” the criminal jurisdiction of the syariah courts is not limited to the violation of the teachings of Islam but can extend to “offences relating to any (of the 25) matters enumerated in item 1 of the State List”.

This appears to be a significant enhancement of power. Many matters like Malay custom which are not criminalised now, could possibly be criminalised in the future!

Federal-state division: Another issue is the demarcation of penal power between the Federal and state legislatures as outlined in Schedule 9, Lists I and II. States have legislative authority to create and punish offences against the precepts of Islam.

But in Schedule 9, List II, item 1 and List I, Item 4(h) this penal power of the states is limited by the words “except in regard to matters included in the Federal List” or “dealt with by Federal law”. Among the matters included in the Federal List are “criminal law and procedure”.

Most criminal offences like murder, theft, robbery, rape, incest, unnatural sex, betting and lotteries are in Federal jurisdiction even though they are also offences in Islamic jurisprudence.

Murder is covered by sections 300, 302 and 307 of the Penal Code. Theft is dealt with by sections 378 – 382A; robbery by sections 390 to 402; and rape in section 375 – 376.

Incest and homosexuality are covered by sections 377A to 377C. State Enactments on these Federal matters are ultra vires (beyond the powers of the states).

The Merdeka Constitution’s scheme was that the states are permitted to punish wrongs like khalwat, zina, intoxication and abuse of halal signs as these are not covered by Federal laws.

Unfortunately, most states are trespassing on Federal jurisdiction by punishing crimes like homosexuality, incest, prostitution, enticing a married woman, betting, lottery and gaming even though these wrongs are clearly part of the Federal Penal Code.

States are also setting up rehabilitation centres even though this power is solely Federal.

Regrettably, such ultra vires state laws are hardly challenged in the courts. In the rare application for judicial review, the superior civil courts are generally reluctant to invalidate laws passed in the name of the syariah.

The Hadi Bill must be seen in this light: it is enhancing penalties for crimes, some of which are far beyond the powers of the states.

Another unresolved issue is that state laws often criminalise acts that are sins, not crimes in Islamic theory. For example, Islam does not mandate criminal sanctions against those who skip Friday prayers or who in honest disagreement, question the desirability of a fatwa (juristic opinion).

Hudud punishments: Under the Bill, what penalties can the syariah courts impose? Specifically, can states impose “hudud punishments” prescribed in classical Islamic law?

The Bill is clear that syariah courts cannot impose the death penalty. Therefore, the non-Quranic penalty of stoning to death is impermissible.

But as the Bill permits “any sentence allowed by Islamic law” (without mentioning these sentences), there is a real possibility in the future of amputations, crucifixions, whipping up to 100 lashes, forfeiture of property, and imprisonment for unspecified periods till the accused repents.

No uniformity: In criminal law there should be uniform application of the state’s coercive powers against delinquents. In the Hadi Bill there is no emphasis on uniformity from state to state. Each state can pick and choose which penalties to impose.

This is a regression from the present position that only three types of penalties (lashes, fine and imprisonment) with strict upper limits can be prescribed in all states.

Kelantan Code: Due to the provision for “any sentence allowed by Islamic law” the Hadi Bill is clearly an adroit attempt to revive the Kelantan Syariah Criminal Code II (1993) which has been lying dormant because of constitutional hurdles.

It is noteworthy that the Kelantan Code of 1993 extends to consenting non-Muslims. This is a serious violation of the Constitution which proclaims that syariah courts have no jurisdiction over non-Muslims.

Jurisdiction is a matter of law, not of consent or acquiescence.

Fundamental rights: As our Constitution is supreme, all Federal and state legislation is subject to judicial review on constitutional grounds. Even if the Hadi Bill crosses the parliamentary threshold, if its content or its consequences are violative of fundamental liberties, judicial review is a distinct possibility.

Thus if two criminals in Kelantan, one a Muslim and the other not, are caught for stealing, the non-Muslim will be tried under the Penal Code.

The Muslim will face the music in the syariah court and may be liable to amputation. Unequal punishments for the same crime would violate the equality provision of Article 8 of the Constitution.

In sum, even if the Bill to amend the 1965 Syariah Court (Criminal Jurisdiction) Act secures a simple majority in Parliament, a Pandora’s box of questions and issues will continue to haunt the legal system.

We can only hope that before the Bill is passed there will be a thorough inquest in our Parliament of the constitutional implications of the Bill.

Shad Saleem Faruqi is Emeritus Professor of Law at UiTM. The views expressed are entirely the writer’s own.