Is it better to live in sub-survival conditions as long as we achieve our racial or religious aspirations?

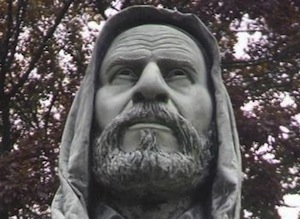

Umar Mukhtar

It is not political ideology or governing philosophy or belief in differing economic regimes that separate Malaysian political parties. It is simply race and religion, period. It is little wonder that in a competitive world of economic wellbeing, we do not have the currencies to emerge on top.

There is not much wrong with that because it can’t be expected that all people all over the world value or go for the same things in life.

Or to put it crudely and unfairly, some racists would rather live in abject poverty as long as their race holds political power. Or it is alright for material comforts of this world to elude some people in this lifetime as long as their eternal comforts are assured in the hereafter.

At first glance, there’s nothing wrong with that either. It’s freedom of choice in a free world.

Except that it is not that clear-cut always. If it is, there would be not much conflict in our societies especially when you allow the next person that freedom of choice as you expect him to accord to you.

The truth is, nobody likes living in poverty if they can help it. Somehow, living comforts remain a priority, even to the extent that it may nullify race and religious loyalties. And the need to impose one’s values on others sometimes borders on forcing rather than convincing.

Maslow, the social theorist, espoused his theory on the Hierarchy Of Needs, that self-actualisation is subordinated to the basic needs for food and shelter. The assumption is that once one has acquired the greater basic needs, one moves on to self-actualisation and modifies one’s behaviour upon attaining the basic needs to reflect one’s philosophy of life and humanity.

The problem arises when people put too much emphasis on the self-actualisation needs even before they can articulate the skills to acquire and comprehend the issues surrounding the more basic needs.

Inevitably, it is all about balance. One need is not mutually exclusive of the other but one modifies the other. The occasional hermit meditating amidst the minimal of what it takes to survive in the caves is an exception rather the rule of the human condition. Sometimes the ugly head of imbalanced priorities rears its ugly head.

My point is simply that one’s chosen leader may be of the race one favours but he is still subject to tests of whether he can ensure the future economic well-being of his flock. Which follows that he needs to be critically appraised. However, in certain segments of our society somehow, because of racial and religious affinities, probing questions to ensure that that wellbeing will continue to prevail, if they come from non-affiliated sources, they are suspect.

To put things simply, ‘outsiders’ cannot question one’s leader even if that leader propagate habits that will run the country or state to the ground. Or non-believers who don’t recognise the divine mandate of one’s religious leader have no business to enquire on his religious logic that may affect everybody’s lives.

Hence, conflicts between political parties in Malaysia that arise in the struggle for mutual benefits are easily mistaken as challenges to one’s actualisation aspirations. In the end, we are all the losers for excluding viewpoints not because of its merits or demerits but because of the source of that viewpoint. We may even lose our basic attainment because of this myopia.

When political parties compete on different planes, eventually the desire for complete homogeneity will invoke destructive tendencies. That may result in our struggle for our basic needs to be threatened by civil unrest. We will not be any better off by this.

In a multiracial and multi-religious country like ours, we have no choice but to rationalise our common basic needs and balance those with our self-actualisation aspirations. To err is fatal.