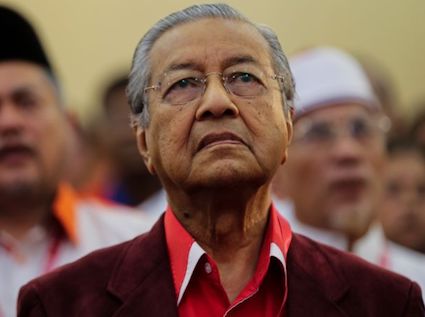

Mahathir 2.0 and the new Malay dilemma

The changing winds of Malaysian politics and the irony of history have now compelled Mahathir to link up with both his historical and more recent political foes to challenge UMNO’s dominance.

Dr Sunil Kukreja, Asia Times

The end of Mahathir Mohamad’s reign as prime minister in 2003 was quite simply a watershed moment for Malaysia. As the fourth prime minister’s 22 years in office came to a close, the country was also poised to move into a post-Mahathir era.

Fast-forward 15 years since his departure from office and Malaysians find themselves having to decide on whether they’re willing not only to embrace a change in government at the federal level for the first time in the country’s history, but also, in the process of doing so, welcome a now 93-year-old Mahathir back into office.

It would be a gross understatement indeed to say that Malaysian affairs have featured some gripping, and at times entertaining, political theater since Mahathir left office. It is equally noteworthy that the elevation of his immediate successor, Abdullah Badawi, followed by the latter’s unceremonious departure and subsequent replacement by Najib Razak, was not without Mahathir’s influence in one manner or another.

Suffice it to say that Mahathir has once again emerged as a serious potential kingmaker in the impending general elections in Malaysia. Having first propped up and then quite relentlessly undermined his understudy, Najib, the former prime minister is now poised to give him a serious run for the office in Putrajaya.

Mahathir’s persistent criticism of Najib over the past couple of years after revelations of serious misappropriation of funds and corruption connected to the now infamous 1MDB (1Malaysia Development Berhad) scandal has ultimately not only brought Mahathir back into the political fray as a contender for office again, but in a strange irony, landed him at the pinnacle of a coalition with the very political opposition he battled against during his time leading the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) and the government.

But so intense and grave had become the schism between him (as well as a small faction of his loyalists from within UMNO) and Najib centering on the latter’s misdeeds, that the country finds itself poised for an election campaign that now pits Najib against his former mentor.

For his part, Mahathir has had to join forces with a coalition consisting of his close allies’ newly formed Bersatu party, the long-standing stalwart opposition Democratic Action Party (DAP) and the Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), the last being the party of the still-jailed Anwar Ibrahim. Of course these latter two parties (and a fair number of its core leadership) were systematically (and some may say mercilessly) suppressed by Mahathir during his time in office.

The changing winds of Malaysian politics and the irony of history have now compelled Mahathir – the consummate political insider and champion of establishment Malay identity politics – to link up with both his historical and more recent political foes to challenge UMNO’s dominance.

Apart from needing to persist and endure the onslaught of UMNO and the state political machinery at its disposal, Mahathir and his newfound Pakatan Harapan opposition coalition are fully aware that their fortunes in the upcoming general elections depend very much on how the Malay electorate breaks. More critically, it will be especially the way the rural Malay electorate goes that will seal the fate of the current government and Mahathir’s opposition coalition.

To be sure, while a second opposition force made up of the Islamist PAS (Malaysian Islamic Party) may well complicate the political calculations in some local races, as there will likely be three-way contests in many constituencies, the present Malay political dilemma fundamentally renders the larger ethnic Malay body politic as rather deeply fractured yet profoundly consequential to determining the make-up of the next government.

The last general elections of 2013 not only bruised UMNO and its governing coalition Barisan Nasional by denying it the popular vote, it also signaled a dramatic shift in the non-Malay electorate. Indeed, it was in large part due to the urban non-Malay ethnic electorate crossing over to the opposition in significant numbers that helped the DAP and the Pakatan Rakyat opposition parties to secure the popular vote.

But given the nature of gerrymandering, where the majority of parliamentary seats remain in rural (and demographically sparse) Malay constituencies, UMNO and Barisan Nasional still managed to capture sufficient seats despite losing the popular vote.

To be sure, Mahathir and the Pakatan Harapan coalition cannot take the broad-based (and largely non-rural) Malay and non-Malay support for granted. However, given the prevailing public discontent, continued intransigence, and the low popularity rating of Najib and his government, Mahathir, the DAP and PKR seem well situated to retain a significant share of backing from the urban-based electorate.

Hence the big unknown this time around remains whether the return of Mahathir (and despite some of the lingering negativity associated with his legacy) will in fact be sufficient not only to not undermine the urban support that the opposition garnered in 2013, but somehow enable them to make a breakthrough with rural Malay voters.

For their part, the willingness of the PKR and DAP to feature Mahathir at the top of the ticket as their prime-ministerial candidate quite simply reflects the game plan of challenging UMNO’s supremacy in the Malay rural heartland. Of course, for PKR and DAP to accept Mahathir into their bid to break UMNO’s grip on power also required some serious soul-searching considering the long-standing adversarial relationship they have had with him.

But if politics tend periodically to make for strange bedfellows, it must also be noted that whatever Mahathir’s motivations may be, the PKR and DAP recognize all too well that political change also requires pragmatism.

Capitalizing on Mahathir’s appeal in the Malay heartland is based on at least two premises: first, that there is sufficient discontent with Najib’s leadership across parts of the traditional rural UMNO base, for example in states like Johor, Kedah and Perak, and second, that a known and trusted champion of Malay rights (like Mahathir) could be a reassuring enough option to pull enough rural Malay voters to cross over and tip the balance in the opposition’s favor.

In a highly racialized political and social system, the fact that the majority of rural Malay voters nationally have never before gambled with supporting any other coalition than the UMNO-led Barisan Nasional is significant. UMNO’s ability to have kept this segment of the electorate secure in its grasp has been imperative – and will remain so – to its political fortunes.

Mahathir’s initial rise to political prominence in the latter part of the 1970s was very directly linked to his articulation of an ideology of Malay chauvinism bundled into a rationalization for special Malay rights both as a security blanket against marginalization vis-a-vis non-Malays and justification for affirming Malay indigeneity. It is precisely this ideology that has become all-pervasive in ensuring UMNO’s grip on much of the rural Malay electorate.

It now appears that the very architect of that ideology of Malay chauvinism will need to convince his brethren why they need to abandon the party that embraced and mastered his politics. Indeed, Mahathir will need to assure them that it is UMNO under Najib that has failed them, and that he has returned only because UMNO has strayed from securing and advancing their welfare.

Mahathir’s political dance will certainly be one not before performed: that he remains steadfastly committed to the future of Malays and Malaysia, and that this impending future must now be once again rescued and secured – much as he did decades ago – under the stewardship of a more dependable and responsible leadership.

Dr Sunil Kukreja is professor of sociology at the University of Puget Sound. His areas of academic expertise include multicultural studies, social and cultural change, and the political economy of South & Southeast Asia. Professor Kukreja has published widely in academic journals and edited several books. In addition, he is editor of a book series titled Modern Southeast Asia, and serves as editor of the journal International Review of Modern Sociology.