Commentary: Beware the deep ironies of the Malaysian opposition coalition

Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s teaming up with other opposition leaders makes for awkward politics – and may come at a cost to the other opposition parties if we look at the 1999 election, says one observer.

Elvin Ong, Channel News Asia

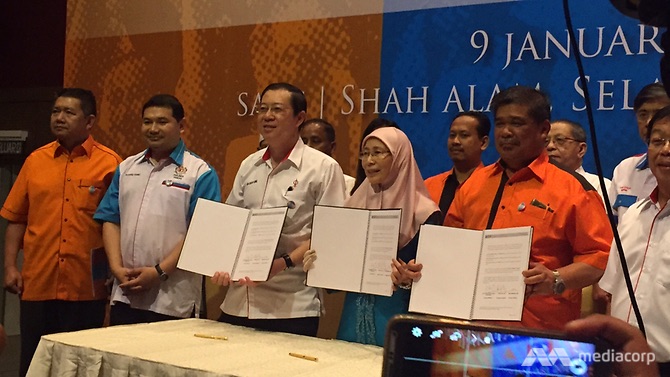

In early March, the Malaysian Pakatan Harapan opposition coalition formally launched its common manifesto, known as the Buku Harapan.

When Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad led his fellow Pakatan Harapan leaders into the convention hall in Shah Alam where the launch event was held, the crowd shouted “Reformasi! Reformasi!” mixed with cries of “Hidup Tun! Hidup Tun!”

More recently, in early April, Pakatan Harapan further announced that all candidates and component parties in the opposition alliance, including the Democratic Action Party (DAP) and Amanah, would jointly campaign and contest in the upcoming general election using a common logo – that of Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR).

This announcement came on the back of the Malaysia’s Registrar of Societies’ statement that Dr Mahathir’s party, the Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia (Bersatu), would be temporarily de-registered for failing to submit proper documentation of its meetings and financial statements.

Close observers of Malaysian politics will immediately notice the deep ironies of these twin developments – Dr Mahathir leading an opposition alliance using PKR’s logo and PKR’s rallying slogan of “Reformasi”.

BACK TO THE 1990S

Back in the late 1990s, “Reformasi” was the clarion call of street demonstrators agitating for an end to Dr Mahathir’s Barisan Nasional (BN) government.

Indeed, the “Reformasi Movement” as it was known, sparked by Anwar Ibrahim’s sacking, arrest and detention, called for eliminating the corruption, cronyism and nepotism of Mahathir’s government.

Mr Anwar and his wife Wan Azizah, subsequently formed PKR as the main party vehicle to channel and organise dissent from the Reformasi Movement to contest in the 1999 elections against the BN and against Dr Mahathir.

Today, the Mahathir-led Pakatan Harapan coalition is campaigning using the logo and motto of the party that was originally formed to oppose Dr Mahathir in the first place.

The ironies do not end there. Mohamad Sabu, Amanah’s leader, Lim Kit Siang and Lim Guan Eng, DAP’s leaders, were all former detainees under Operation Lalang, a security crackdown executed in 1987 under Dr Mahathir.

These leaders were all on the same stage with him when the opposition coalition’s manifesto was launched, and are now found regularly sitting beside him at press conferences and nightly ceramahs throughout the country.

How does one begin to demystify this perplexing twist of fate in Malaysia’s most recent electoral politics? Why have such strange bedfellows come together to oppose the current BN government?

NO PERMANENT FRIENDS OR FOES

One interpretation of these events is that these leaders have all realised that they can achieve their common aims of defeating the incumbent BN and remove Prime Minister Najib Razak only if they cooperate with each other.

Thus, observed cooperation is an outcome of the recognition of common goals.

Yet, although an identification of shared objectives is oftentimes a necessary ingredient of alliance formation, it is not sufficient. A more nuanced and complete interpretation for the puzzling turn of events is that it is a reflection of a common adage:

In politics, there are no permanent enemies and no permanent friends. Only permanent interests.

In other words, it is the confluence of self-interest between both Dr Mahathir and the other opposition leaders that have brought them together. All believe they stand to benefit in campaigning jointly with each other to signal to voters a common opposition against the existing BN administration.

WHATEVER IT TAKES

On the one hand, Dr Mahathir is willing to do whatever it takes to signal to voters his commitment to the opposition’s cause.

There remain doubts in the minds of some opposition voters about whether he would renege on the opposition’s reform agenda if he were to become prime minister, or if his party would disavow the opposition alliance if it were to lose the elections.

Publicly apologising for his “past mistakes” of his premiership from 1981 to 2003 can only go so far to assuage these voters of his commitment.

By forging deeper forms of cooperation through using a common logo, a common manifesto, or by endorsing other opposition leaders, Dr Mahathir can more credibly ask for the support of both hardcore and moderate opposition supporters.

In a highly uncertain election where every vote counts, support from the non-Malays even in Malay-majority constituencies, will be crucial. If Dr Mahathir can credibly signal a commitment to the opposition’s cause by publicly tying himself to the opposition’s fate, then non-Malay voters may be willing to “hold their noses” to vote for him and Bersatu’s candidates.

Likewise, on the other hand, through ever deeper forms of cooperation with Dr Mahathir and his Malay-bumiputera-only Bersatu, other component parties of the PH alliance too stand to benefit.

The Chinese-based DAP, in particular, recognises that it cannot hope to be part of any future government if it contests alone. Its candidates, particularly those contesting in ethnically mixed constituencies, will need substantial Malay support to stand any chance of winning, particularly Malays defecting from the BN.

Tying themselves to the pro-Malay Dr Mahathir may help reassure and mobilise moderate Malay voters to similarly “hold their noses” to turn out and vote for DAP candidates.

SIGNIFICANT COSTS, SACRIFICE

To be sure, the DAP, PKR, and Amanah incur significant costs when they are seen by some supporters to be too closely allied to Dr Mahathir and Bersatu.

Hardcore opposition supporters who cannot forgive Dr Mahathir for the past policies instituted during his 22 years as Malaysia’s prime minister may choose to defect to other minor parties or not turn out at all.

They believe that working with Dr Mahathir is too much of a sacrifice of their commitment to democracy and race-free politics, even if that short-term compromise may bring about long-term political gains.

Some may even find the #UndiRosak movement, which calls for voters to spoil their votes, to be a more palatable option.

Recall that the DAP once suffered a serious backlash among its own supporters when it forged an alliance with PKR and Parti Islam se-Malaysia (PAS) for the 1999 general elections. Its candidates fared poorly, while its party leaders Lim Kit Siang and Karpal Singh both lost their parliamentary seats that year.

Much will depend on whether these opposition party leaders can persuade their core supporters to stay within the fold even as they simultaneously reach out to new sources of voters for support.

If opposition party leaders can successfully accomplish these twin tasks, then their prospects for defeating the BN will surely be enhanced.

Elvin Ong is a PhD candidate in Political Science at Emory University, and an NUS-Overseas Graduate Scholar. This commentary is the first in a series of commentaries by the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) on the 14th Malaysian General Election.