For Anwar, a roller-coaster life takes a new turn

(AP) – Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim’s release from prison marks yet another dramatic turn in a roller-coaster political life that has left a profound mark on Malaysian politics and society.

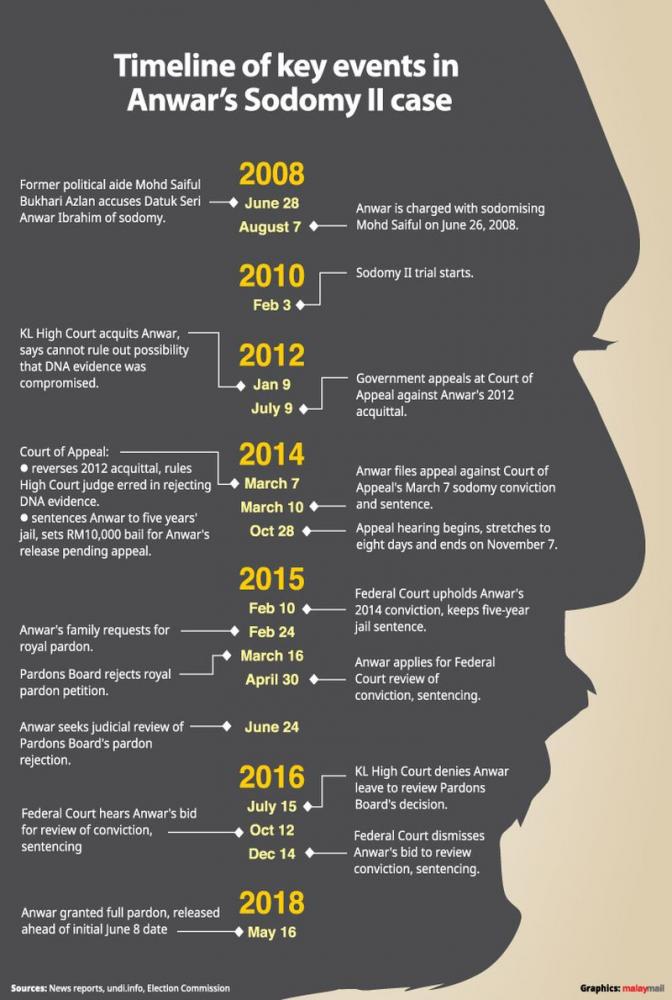

The opposition figurehead was freed today after serving three years for a sodomy conviction widely viewed as politically motivated, and now quashed in the wake of the stunning defeat of the regime that ruled for six decades.

Anwar’s political triumphs and legal tribulations have riveted and appalled Malaysians since the 1990s, when he soared to national power as a talented deputy prime minister, then fell spectacularly, only to rise from the ashes in the opposition.

Anwar has come tantalising close to leading the nation before but those hopes now look as strong as ever, with 92-year-old new Prime Minister Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad signalling he will yield to his one-time protege in one of the great turnabouts in Asian politics.

Just three years ago, Anwar’s career seemed finished, once again, when he was jailed on charges of sodomising a young male aide — the second time he had faced such charges.

“Going to jail, I consider a sacrifice that I make for the people of this country,” he said at the time.

“I have fought most of my life on behalf of the people of this country — for the people, I am willing to go to jail or face any other consequence.”

— Political chameleon — In his four-decade career, Anwar has changed his political colours with the readiness of a chameleon in an ambitious pursuit of leadership in the multi-ethnic, Muslim-majority country.

He first rose to prominence in the 1970s as a radical Islamic student leader, taking part in protests over rural hunger that earned the first of his three jailings by Malaysia’s authoritarian regime. He was held for 20 months under a draconian security law.

But he later shocked many associates by joining the ruling United Malays National Organisation (Umno), and eventually caught the eye of Mahathir, the tough leader who dominated politics from 1981 to 2003 and has continued to exert formidable influence.

A gifted natural politician and witty orator, Anwar rose quickly, heading various ministries including the finance portfolio starting in 1991, while reinventing himself as a reformist who was praised in the West.

Two years later, his ascension to deputy prime minister all but anointed him as Malaysia’s future leader.

But differences with the proud Mahathir over how to respond to the 1998 Asian financial crisis spiralled into a bitter rift as Anwar called for reform and an end to Umno corruption and nepotism.

Anwar was seen to have misplayed his hand, underestimating Mahathir, and he was sacked and charged with corruption and sodomy.

In a drama that earned worldwide scorn, Anwar was brought into court with a black eye after a beating from the country’s police chief.

His bruising fall was widely seen as politically motivated, and triggered unprecedented protests in a country where dissent was suppressed.

Jailed for six years, Anwar says he was kept in solitary confinement, singing 1960s pop tunes to stay sane and reading anything he could get, including the Quran, the Bible, and Shakespeare.

Released in poor health in 2004 when the sodomy charge was overturned, the father-of-six spent a few years recuperating and working as an academic.

But he eventually joined the anti-government movement that had been energised by his ordeal, using his star power to unite a divided and cowed opposition.

Their three-party alliance capitalised on rising anger over corruption and Umno oppressions to shock the regime in 2008 and 2013 polls.

It stung Umno by winning 52 per cent of the popular vote in 2013 but failed to take parliament due to government gerrymandering.

— Strange bedfellows — The opposition alliance united by Anwar brought together strange bedfellows — an ethnic Chinese pro-democracy party, the conservative Islamic PAS, and Anwar’s own racially diverse party.

With his broad appeal across Malaysia’s various ethnic communities, he was considered the glue holding the alliance together.

The corruption-plagued former government of now-disgraced Datuk Seri Najib Razak was keenly aware of this, and the latest sodomy charge dogged Anwar through a lengthy trial that culminated in his jailing in 2015.

Many observers viewed the charges as an attempt to decapitate the newly potent opposition, which was fuelled by public disgust over government corruption, rights abuses, racially divisive politics, and increasingly authoritarian tactics.

Sure enough, not long after Anwar’s removal, the tenuous opposition alliance crumbled amid internal dissension. Hopes of throwing off Umno’s yoke seemed crushed.

But in one of Malaysia’s many political twists, Mahathir came out of retirement, determined to oust Najib over accusations that the former premier presided over the looting of billions of dollars from a state investment fund, a scandal that has tarnished Malaysia worldwide.

The public responded, throwing out Umno in a landslide, and putting Anwar on course to finally achieve his dream of leading Malaysia.