The Tunku and I

A Kathirasen, Free Malaysia Today

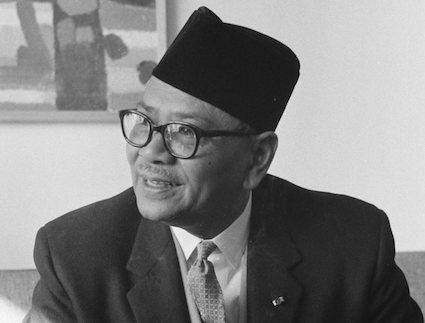

Whenever Merdeka comes around, we can’t help but remember the founding fathers, especially Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra al-Haj, the father of independence and the first prime minister.

I am one of those fortunate enough to have met the Tunku, on a few occasions, even though this was long after he had retired as prime minister.

I was working in Penang in the 1980s, and it was not too difficult to get an appointment to see him as his aide-de-camp Owen Chung, with his distinctive handlebar moustache, was rather accommodative.

In 1985, a group of us who were members of an organisation called the Penang Indian Cultural and Arts Society, arranged for, and celebrated, his birthday at his home – with a cultural show and plenty of food.

He was elated, as were those present to wish him happy birthday. His conviviality and humility touched all of us, as he enjoyed the food that was served and the dances and music that were staged.

It was such a joy to see his joy. For this was the time when he was not exactly a friend of the state, which was then led by Dr Mahathir Mohamad.

On one occasion, the Tunku opened up and told me about how people who had been close to him in earlier years had now distanced themselves. This was especially so with Umno leaders and members. His enquiries, he told me, revealed that most of them were afraid to be seen with him as the Umno leadership was against it.

Sadness and hurt were clearly etched on his face as the Tunku told me about how his “friends” had abandoned him, either to curry favour with Dr Mahathir or out of fear that this would irk him.

I found out from Chung and others that only a few people called on him during this period, mostly non-Malays.

Dr Mahathir, of course, was Umno president then. To say the two leaders have never had a good relationship would be an understatement.

When the Tunku was prime minister, Dr Mahathir agitated against him and his policies, and when Dr Mahathir was prime minister, the Tunku was critical of him and his policies.

The first time I met the Tunku, I was self-conscious as I was meeting a former prime minister, the father of independence. But he made me feel at ease and, although he was much older than I, he treated me as he would a friend. I suppose his use of simple language, as was his wont, and his honesty and friendliness, helped achieve this.

I’d like to share three valuable lessons I learned from these meetings. When you are in power or position, you always attract a crowd, you have plenty of friends; but when you have no power, many of these friends disappear.

I’d like to pass this lesson from the life of the Tunku to Pakatan Harapan leaders: be aware that you are surrounded by many people today not because you are great or a lovable personality, but because you have power and they can benefit from it. Don’t forget your real friends – those who were with you when you were struggling as part of the opposition and when you were being harassed, even dragged to the courts, by previous governments.

Coming back to the Tunku, despite feeling he was being treated unfairly, he continued to believe in the goodness of people and he never lost hope for a united and happy Malaysia.

And that is the second lesson I learned: to never lose hope in the goodness of people.

His main theme was always unity.

For instance, he told those who threw the birthday party to consider themselves Malaysians first and foremost and to give thanks that they were living in a wonderful country. I still remember him saying: “We must always live and let live. We must respect each other and help each other so that we can live happy lives. I want everyone to be happy.”

In fact, this was the main goal of the Tunku’s nation-building effort: to head a nation of happy Malaysians. He is reported to have said that he was the happiest prime minister.

The Tunku told me that Malaysians should use the diversity of races and cultures to enrich the nation. He said the inherent strengths of the different races, if properly combined, would put Malaysia ahead of others in socio-economic development, and that he had seen this happen during his time as prime minister.

“Whatever we do,” he said, “We must think of Malaysia – whether our actions will harm or heal.”

During another chat, he used the simple analogy of a boat to relay this message to me, probably realising, or hoping, that as a journalist, I would pass it on.

“Malaysia is like a boat. If the boat sinks, we will all sink. So we have to keep it afloat. We have to co-operate; joint effort. We have to row together. If water gets in, we have to scoop it up and throw it out together. Then we will be safe and happy. That is what I want for this blessed country.”

He hoped that Malaysians of all races would realise this and get along with a “live-and-let-live” attitude so that we could be a nation of happy people.

He had expressed similar sentiments in public from the time he was prime minister.

Talking about the Alliance party, he once said: “For us in the Alliance, we have no dogmas other than to ensure happiness for the people.”

And this is the third lesson: live and let live.

As I grow in years, I realise how important such an attitude is in the family, in society and especially in a nation of diverse races and religions.

So, as we celebrate Merdeka, let us remember the Tunku and the founding fathers and their sacrifices. Let us follow the Tunku’s policy of “live and let live” and let us try to make this a happy Malaysia.

A Kathirasen is executive editor at FMT