What has become of Dr Mahathir’s promised reforms?

The underwhelming economic plan comes against a broader backdrop of the Pakatan Harapan (PH) administration walking back on promises it made in the heat of the election campaign earlier this year. More troubling than the revival of controversial policies from yesteryear, however, is the fact that Dr Mahathir and his new PH coalition are struggling to live up to their campaign vows.

Alistair Denness, Asian Correspondent

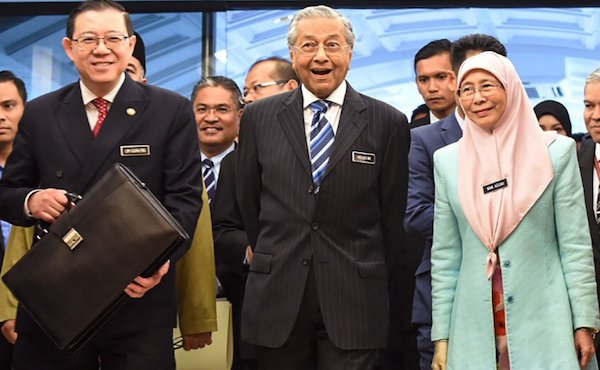

JAPANESE Prime Minister Shinzo Abe offered a lifeline to his Malaysian counterpart this week, telling Dr Mahathir Mohamad that Tokyo is ready to extend Kuala Lumpur JPY200 billion (roughly US$1.8 billion) worth of bonds.

The promised securities should somewhat reassure Malaysians worried about the country’s mountain of debt.

Japan’s offer of financial assistance is also likely to be a relief to Dr Mahathir’s government, which has been struggling to defend its 2019 budget against allegations that the long-awaited economic plan is a “copy-paste” budget which analysts suspect does not go far enough to shore up the country’s troubled economy.

More troubling, the underwhelming economic plan comes against a broader backdrop of the Pakatan Harapan (PH) administration walking back on promises it made in the heat of the election campaign earlier this year.

Controversial economic policies

Part of analysts’ concerns over the recently-released budget have to do with the fundamentals of Dr Mahathir’s economic policy.

The 93-year-old statesman, who previously ran Malaysia with an iron fist from 1981 to 2003, pulled off a surprise victory in May by casting himself as a “reformer ready to move ahead after apologising for the mistakes of the past”.

While Dr Mahathir may have evolved on questions such as the freedom of the press—his prior tenure as prime minister was marked by significant censorship—his economic stratagems seem to have changed little.

Some of Dr Mahathir’s unconventional economic decisions—his bold move to peg the ringgit to the US dollar in the midst of the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, for example—paid off.

Others, such as his enduring obsession with creating a Malaysian national car, have been catastrophic failures.

The resurrection of the national car project—in the face of significant public opposition, Dr Mahathir defended his auto manufacturing dreams by asking Malaysians if they wanted to be “a country of peasants”—as well as the continuation of affirmative action programmes favouring Malays and the scrapping of the goods and services tax (GST) which accounted for 3 percent of the country’s GDP have left investors skittish.

An apparently overambitious manifesto

More troubling than the revival of controversial policies from yesteryear, however, is the fact that Dr Mahathir and his new PH coalition are struggling to live up to their campaign vows.

Dr Mahathir has openly backpedalled on a number of electoral promises: the PH manifesto enumerated 10 changes it would implement in the party’s first 100 days in power and 60 it would institute over the course of five years.

While some have been achieved, many others have been left by the wayside – a discrepancy Dr Mahathir has attempted to explain away by confessing that the manifesto was written with the expectation that he would not win.

Some of the broken promises can be put down to budgetary constraints, such as Dr Mahathir’s admission that he would not be able to create toll-free roads, as pledged during the campaign, without simultaneously increasing petrol taxes.

Others, however, are more ideological in nature, such as the premier’s backtracking on granting opposition leaders the same status as ministers. That pledge, Dr Mahathir conceded, was only made on the assumption that his own party would comprise the opposition.

Particular priorities

Despite his inactivity on many of those key promises, Dr Mahathir has aggressively pursued other priorities, such as prosecuting his predecessor Najib Razak in connection with the 1MDB scandal.

Critics have claimed that Dr Mahathir’s rigorous investigation into Najib is motivated more by a personal vendetta against his former protégé than by a sudden passion for eradicating corruption.

It’s an argument supported by certain worrying elements in the case—such as the fact that Najib’s defence was only given an hour to study recent charges brought against him—as well as by Dr Mahathir’s history of going after political allies-turned-rivals.

In any case, prosecuting Najib is unlikely to do much to allay Malaysians’ concerns over PH’s broken commitments. As one woman recently told The Malaysian Insight, the new government “has promised many things but hasn’t delivered […] Their Budget 2019 is nonsense and doesn’t help the youth or senior citizens.”

Given that Malaysian voters’ primary concern for years has been the economy, this disillusionment risks causing serious problems for the ruling coalition further down the line.

Against all odds, Dr Mahathir managed to convince Malaysians that he had turned over a new leaf and was the best hope of ensuring the stability of the country’s finances.

As the East Asia Forum underlined, “if ever a government had the mandate and popularity to progress a bold reformist economic agenda, it is now”.

PH’s first six months in power—and in particular the 2019 budget—suggest that it may not be prepared to take advantage of this remit.