Malaysia’s market calm may be shattered as oil turns lower

The ringgit and stocks have remained relatively stable thanks to the rising price of oil. With that support removed, things could get messy.

(Bloomberg) – Malaysia’s Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad has been lucky, so far.

His country looks to have come out of this year’s emerging-markets rout largely unscathed. The ringgit has fallen only 3.4 percent against the dollar, while the MSCI Malaysia Index has dipped a mere 5.9 percent, compared with a 16 percent slump for the broader emerging-markets gauge.

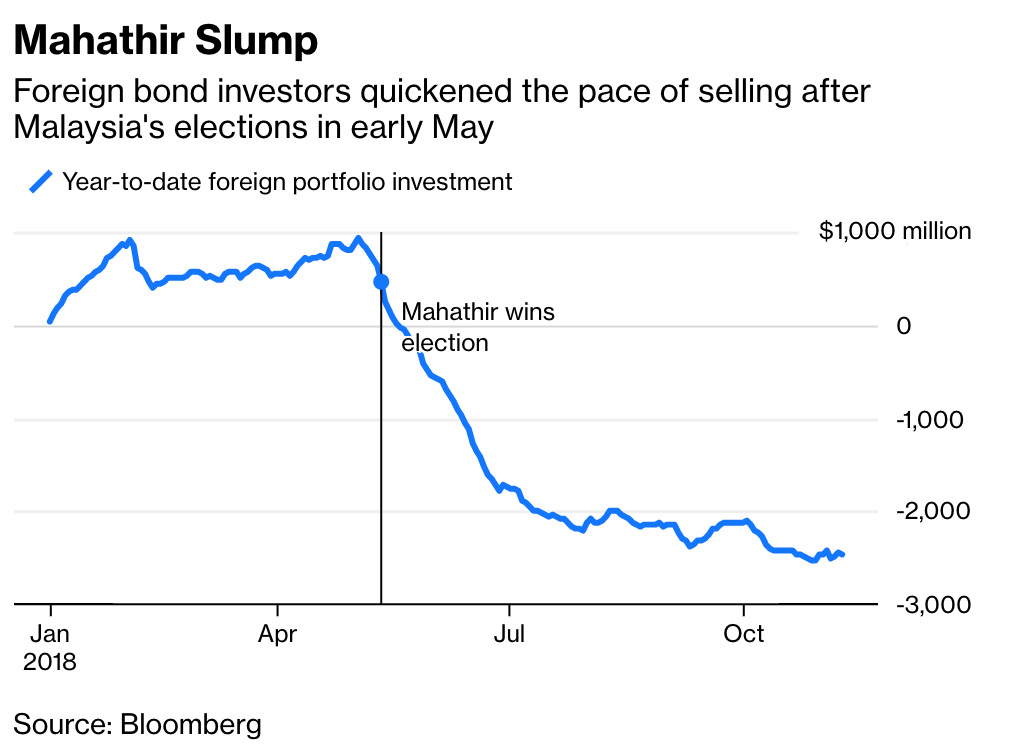

Beneath the calm is a steady exodus by foreign investors, though. They started selling Malaysian bonds as soon as Mahathir won the May election, driving cumulative withdrawals this year to almost $3 billion.

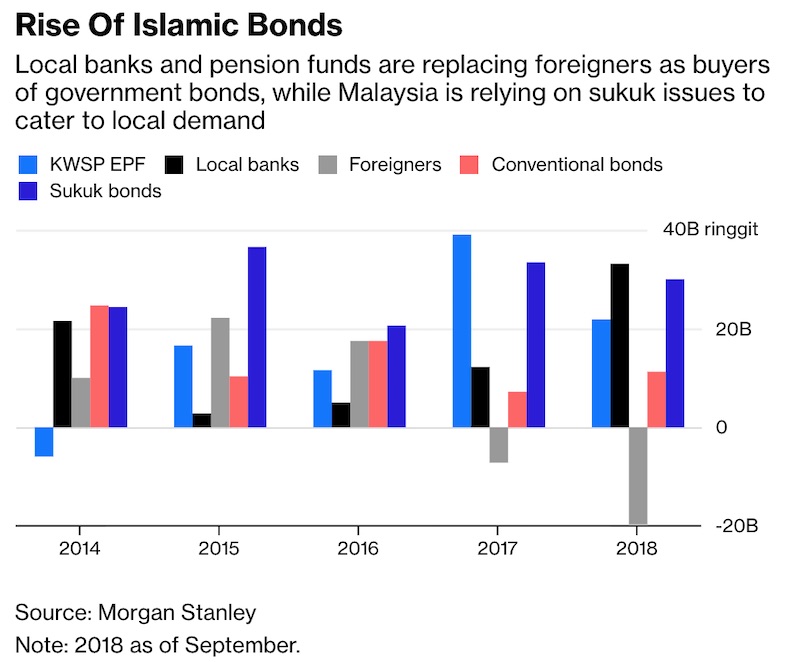

To plug the hole, the government is increasingly relying on local demand, by issuing sukuk, or bonds that comply with Islamic law. As of 2017, the $195 billion Employees Provident Fund had 23 percent of its assets allocated to government debt, from only 18 percent three years earlier.

One can’t help questioning whether Malaysia can become self-reliant. Mahathir certainly thinks so, having canceled the Chinese-funded East Coast Rail Link after campaigning against undue influence from the nation. That decision alienated Beijing, a driving force behind foreign direct investment in Malaysia in recent years.

But foreigners still owned about 23 percent of Malaysian government bonds as of September — a high proportion by international standards. These investors are being spooked by the prospect of a twin deficit, a taboo that Mahathir is testing.

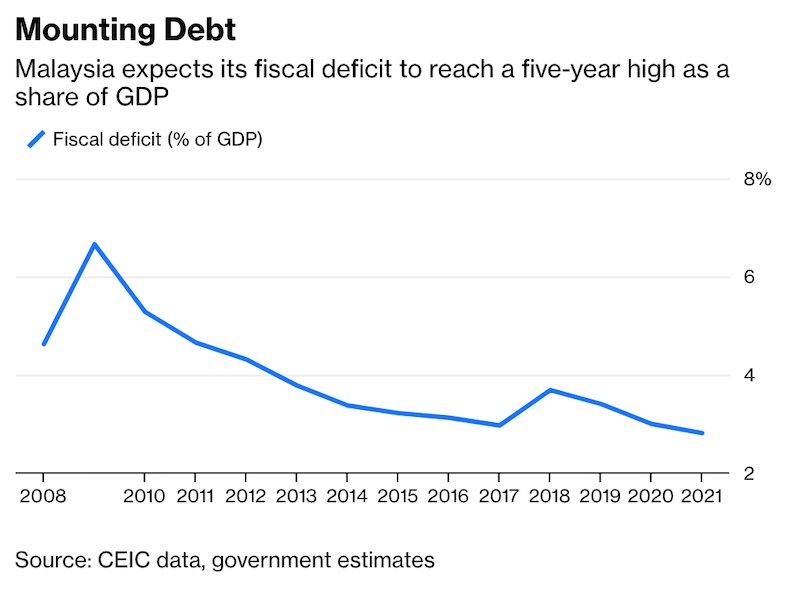

The country is pushing its budget deficit to the highest in five years. Meanwhile, its current account surplus will undoubtedly narrow if the bear market in oil persists.

To be sure, Mahathir was dealt a bad hand by the government of his predecessor Najib Razak. Collectively, the 70 billion ringgit ($16.7 billion) he needs to shell out to service tax refunds and debt payments on behalf of troubled state fund 1MDB account for 30 percent of government income.

The new government is adding to the pressure, though. Mahathir repealed a 6 percent goods and services tax that contributed about 20 percent of the government’s total income last year.

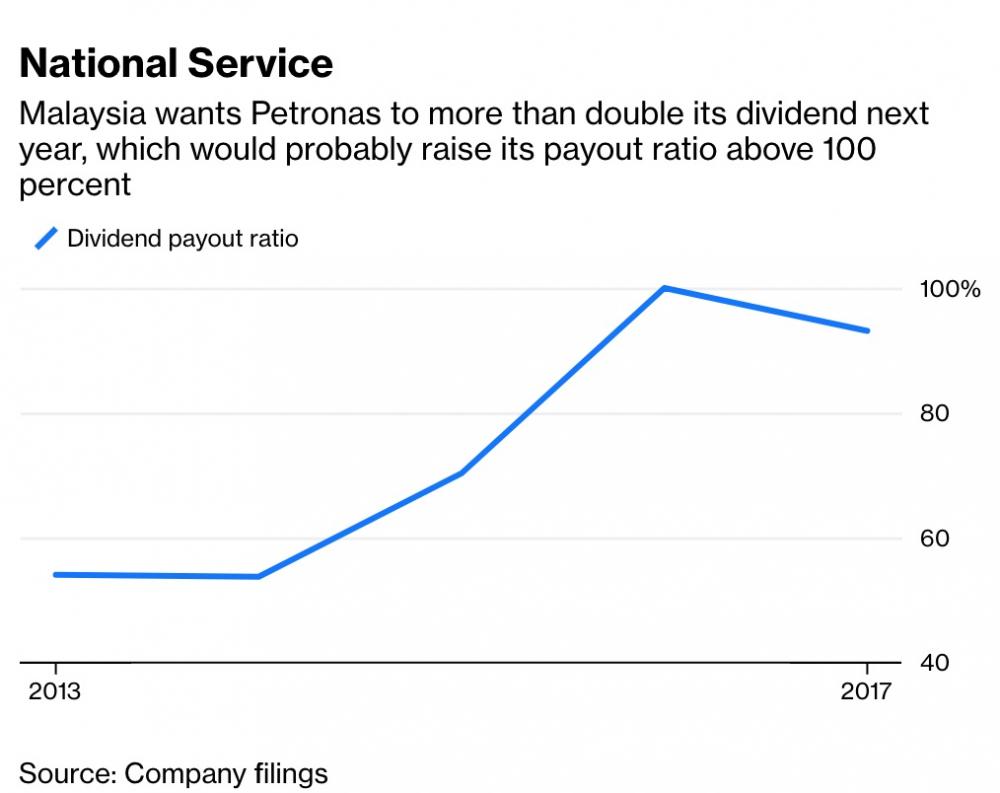

The tax burden will fall instead on state-owned oil and gas giant Petroliam Nasional Berhad. The government plans to claw out 54 billion ringgit in dividends from Petronas next year, double the 26 billion ringgit it received in 2018. That’s a big ask, given the company’s 93 percent payout ratio and falling oil prices.

To make matters worse, similarly rated oil exporters from the Gulf will be entering JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s emerging-markets government bond indexes next year. Unlike Malaysia, Saudi Arabia is narrowing its fiscal deficit faster than expected, while Abu Dhabi will record a surplus soon.

Meanwhile, putting a larger share of Malaysia’s pension fund into fixed-income may not be serving the country’s interests. Most of the world, including Japan and South Korea, is walking the other way. The best-performing pension funds last year had the highest proportion of assets in equities, according to a recent study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Malaysia’s calm has been underpinned by rising prices for its oil exports. As the black gold hits the skids, we may start to see what a fragile veneer that was.