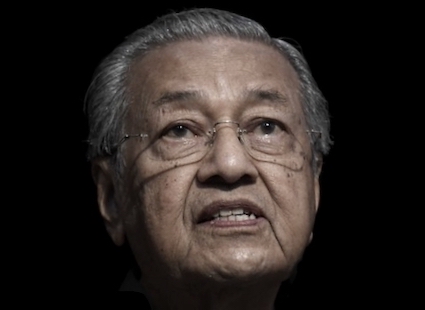

A year since victory, can Mahathir run Malaysia’s economy without blaming Najib or ‘1MDB mess’?

South China Morning Post

“It won’t be a celebration, more of a reflection.”

That is how a senior member of Malaysia’s government described the televised speech Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad is expected to deliver on May 9, the first anniversary of the Pakatan Harapan coalition’s stunning election win.

The government official said the address – yet to be publicised – would be billed as a “state-of-the-union type of speech” and would list the administration’s successes since it toppled the Barisan Nasional bloc that had dominated the country’s politics for six decades.

Among the achievements that the 93-year-old comeback prime minister is expected to coo about is his government’s swift action over the multibillion-dollar 1MDB corruption scandal – including the 42 criminal charges levelled against his deposed predecessor Najib Razak, a one-time protégé.

But with one leading think tank on Friday reporting the government’s approval rating had plunged to 39 per cent from 67 per cent last August, some humble pie will have to be eaten too, according to Mahathir’s critics as well as his lieutenants.

The top question the administration is battling is whether it has the economic management chops to steward Southeast Asia’s third largest economy.

Recent macro indicators suggest slumping investor confidence as May 9 nears.

Data from the local firm MIDF Research this week showed weekly net foreign selling of local equity had reached a six-week high – with year-to-date outflows of some 2.5 billion ringgit (US$600 million). Investors in neighbouring Philippines, Indonesia and even Thailand – facing a post-election political quagmire – were net buyers of local equity in the same period. The ringgit has also been beset by a sell-off amid fears Malaysia will be removed from a prestigious global bond index over liquidity concerns.

Economic watchers on both sides of the political divide, and independent analysts, say they are caught up in internal debate over what exactly is battering market sentiment.

Wong Chen, a member of parliament from Mahathir’s coalition and one of the early drafters of its economic manifesto, acknowledged that global headwinds were one reason for the sombre outlook as the government’s first anniversary nears.

Another factor is one the coalition already anticipated.

As a result of its abolition of a Najib-era goods and services tax and subsequent introduction of a sales and service tax – with a three-month tax holiday in the interim period – the government had to bear a fiscal gap of some 20.5 billion ringgit, Wong said.

That caused some nervousness among rating agencies, despite Pakatan Harapan’s assurances it would recoup the lost revenue in the medium term by clawing back leakages from corruption and raising income levels. Malaysia’s GST, installed in 2013, generated about 18 per cent of government revenue in 2017.

Beyond the fiscal gap issue, however, Wong said the administration’s top economic managers should do some soul searching on the signals they had been sending to investors. If the government followed through with delivering rapid political reform – as it promised when it came to power – investors may be singing a different tune, he suggested.

Mahathir has said he was puzzled by such criticism because the government had been preoccupied with cleaning up the “mess created by 1MDB”, and other reforms had been slowed down because of the sheer scale of that exercise.

The Pakatan Harapan government said it was left with a debt of more than a trillion ringgit, which it blames on Najib’s alleged profligacy and corruption.

But Wong said the government could not keep pointing the finger at Najib for much longer when questioned about the slow pace of reforms.

“Financial reforms are difficult, because you need money,” the lawmaker said.