Mahathir sudah tak logik

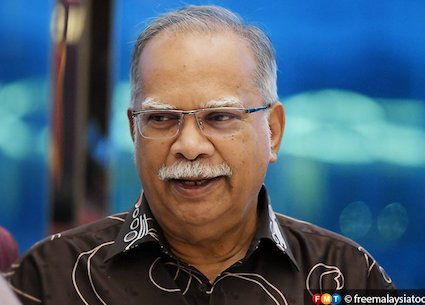

P Ramasamy, Malaysiakini

Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad might be less and less right on international affairs than he was ever before.

The argument of interference into the internal affairs of countries cannot be sustained because leaders have the moral right to speak on matters concerning the moral, humanitarian, social and economic deprivation of communities and ethnic and religious groups.

However, there is a caveat to such commentaries as they must be based on facts, not on political expediency.

Mahathir has recently raised his concerns about the plight of the Muslims in Jammu-Kashmir as result of the imposition of direct rule by New Delhi and the impact on the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) on Muslims, but he has refrained from raising the matter of the discrimination of non-Muslims in Muslim-dominated states like Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan and others.

Where Muslims are minorities, he thinks that the best form of government should be based on principles of secularism but it is legitimate to have theocratic states where Muslims are in the majority.

Now, what kind of logic is this?

Mahathir wants to act as a spokesperson of Muslim matters in the global arena.

Nothing wrong with this as the archaic principle of non-interference must give way the discussion of humanitarian issues.

But unfortunately, with the exception of China, Mahathir seems more predisposed in talking about the plight of Muslims in countries that have Muslims as minorities.

Of late, India with its huge Hindu majority has been the target of Mahathir’s criticisms.

Interference into the affairs of other countries can be defended if facts are right.

Again, when it comes to the twin issues of Jammu-Kashmir and the new citizenship law, Mahathir has not been well informed.

How could he talk of India’s invasion of the territory when the state was ceded to India in the immediate aftermath of independence.

It was Pakistan that invaded the province only to be repulsed by India. Who are the real invaders of this territory?

How can the new law on citizenship which seeks to address years of discrimination of non-Muslims in the Muslim theocratic states of Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan can be termed as anti-Muslim?

As it is, no Muslims or non-Muslims are deprived of applying through the normal channels as provided for in India’s secular constitution.

The new citizenship law is a special one meant to address a specific long-standing problem of religious discrimination, forced conversions and displacement in the theocratic countries mentioned.

The CAA is not perfect as it does not address the plight of other minorities in countries like Myanmar and Sri Lanka.

More than one hundred thousand refugees are in refugees’ camps in India with no prospect of going back to Sri Lanka. Shouldn’t something be done to resolve their long-standing problem?

Mahathir as every right to raise matters in international fora, but he must be seen as fair and responsible.

He just can’t raise matters based on political expediency or to enhance his reputation in the Muslim world.

He cannot side-step the discrimination of Uyghurs in China or the desperate situation of Yemenis as a result of the assault by Saudi Arabia and others.

The Muslim world is not perfect as the denominational warfare between the Sunni and Shia shows no signs of let-up.

It is hardly appropriate for some analysts to take the present appeasement politics in India as a sure sign of disenchantment with the Narendra Modi government. Indian democracy provides more room for dissent than any other countries.

In a specific sense, the leaders of the Congress Party have no moral standing in opposition to the new citizenship law as they cannot hide their role in the division of India on a religious basis.

While Pakistan and Bangladesh, the then East Pakistan, embraced Islam as the basis of political governance, India remained as the bastion of secularism and home to the second-largest Muslim population in the world, second to Indonesia.

Who said that Muslims have no place in India? They have as much right as the Hindus under the country’s constitution, the supreme law of the land.

It is not the question of a blind right to say things, but whether such a right can be justified on high moral principles and whether the right to say is backed by solid facts.

In the absence of these two criteria, there is no automatic right to say things and get away with it.