The truth about the Chinese migration to Malaya

Wong Tai-Chee, MySinChew

Last year, out of kind intention, primary industries minister Teresa Kok urged Chinese Malaysians to treat our migrant workers well with a thankful heart because our own ancestors were also migrant workers from China, who had to brave the utmost trials and tribulations to begin a new life in this new country and made significant contribution towards its development.

Soon after the minister made the statement, some local Chinese who have a strong sense of pride began to voice their disapproval, arguing that migrant workers we have here today are not quite the same as the early migrants from China, and in no way should they be compared alongside today’s migrant workers who are perceived to be at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

Such comparison, they feel, is totally humiliating and unacceptable.

Well, let’s explore this issue from the perspective of the country’s economic history.

Undeniably, the Chinese have the deep-rooted tradition of defending their dignity and the honour of their ancestral families. Even though they are now living outside China, this age-old philosophy still thrives.

Scholars researching the history of the country’s Chinese community tend to glorify the early migrants in their reports for fear any unglamorous descriptions will land them in trouble, especially at a time Chinese Malaysians are fiercely safeguarding their own community rights and interests. Anyway, highlighting own community’s deficiencies and shortcomings will only diminish our sense of pride. Won’t it?

Having said that, it is also a virtue and courageous act to feel ashamed of our own shortfalls.

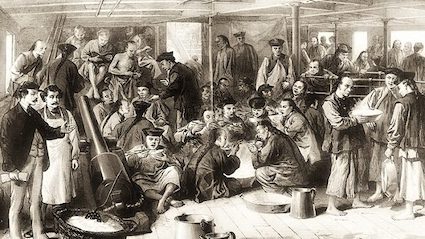

The phenomenon of large numbers of Chinese coolies flocking to Malaya after mid-19th century basically satisfies both the pull and push factors in Malaya and China respectively.

Among China’s push factors were abject poverty and lack of arable lands for the local farmers resulting in very tough life for most people. After the Opium War, the Qing dynasty government began to loosen its grips on the long-standing coast control policy, giving coastal farmers extended freedom to exploit the opportunities beyond. The Treaty of Nanking signed after the Opium War opened up the seaports of Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai for external trade, while sending some kind of signal to people yearning to embark on a seafaring venture to the South Seas, especially those living in densely populated Pearl River Delta, along the Han River, in the mountainous province of Fujian as well as the Hakka settlements in the mountains along the border between Guangdong and Fujian provinces.

As for the pull factors, Malaya had a migrant-friendly policy granting legal migrants the right to seek employment here. Large numbers of Chinese migrants arrived in Malaya after mid-19th century to satisfy the demands of the economic development as well as the imperialistic expansion of the colonial masters.

Following the accelerated industrialisation of Britain, its demands for foreign raw materials surged, and the colonisation of Malaya gave rise to the expansion of economic activities from coastal seaports to mining and agriculture in the hinterland.

In addition, the opening of Suez Canal and the invention of steam engine further shortened travelling time and cost, marking a new milestone for British capitalism.

I need to emphasise here that there were actually very few Chinese migrants prior to mid-19th century, mostly merchants. Some of them married the local Malay women but still retained their own religious beliefs and their baba and nyonya identities. Nevertheless, a small part of them were converted to Muslims and became naturalised Malays.

Studies showed that the period of time between 1880 and 1940 marked the peak of the migration season for the Chinese. Based on the migrant and Malayan Chinese population ratio of that time, the intake of migrants into Malaya was several times higher than the emigration of Europeans to America.

The sudden influx of diligent yet impoverished and lowly Chinese migrants with strong affinity to their ancestral origins gave rise to a binary phenomenon as the economic development in the colony provided them unprecedented opportunities to get rich.

On one end of the spectrum were elite Chinese business leaders who were scarcely educated and were therefore denied access to government posts but somehow managed to create their wealth from the boundless business opportunities in colonial Malaya’s economic realm. As such, for those with business acumen and an independent spirit, the meagre capital they managed to save up from their coolie jobs would take them into the agriculture, mining and business sectors like the colonialists, once they sense the opportunities knocking at their doors.

The local Chinese leaders applied to the Malay rulers for the right to develop agricultural lands in order to grow economically feasible crops such as rubber. During the first two decades of the 20th century, most of the rubber estates were owned by the Chinese before the Europeans took over.

Another business dominated by the Chinese during the early years was tin mining. In early 1860s, Ghee Hin and Hai San companies were granted the mining rights by the Sultan of Perak. However, due to the several violent clashes between them that resulted in thousands of casualties and injuries,the British found an excuse to mediate and intervene in the state administration. The British forced the Perak Sultan, Ghee Hin and Hai San to sign the Pangkor Treaty in 1874 to accept a British Resident to “advise” the Sultan in state administration. Very soon the Europeans’ tin production overtook that of Chinese companies.

Such a development could be blamed on the weak political awareness and limited capital of the local Chinese businessmen as well as their traditional way of running the business and lack of financial support from banks. Moreover, many early Chinese entrepreneurs maintained direct or indirect relationships with the secret societies, and they adopted a more traditional and conservative style of management, controlling the lower segment of the society which formed the majority of the local Chinese population, who were at the other end of the social spectrum.

The Malayan Chinese community was a relatively “autonomous” entity during the pre-war years. The British fundamentally took the laissez-faire approach in management in a bid to slash administrative cost.

Against such a backdrop, the colonial government appointed a local Chinese leader as Kapitan to handle the civic conflicts within the Chinese community, but the colonial government might step in whenever necessary, for example the 1916 bloodshed arising from the labour contract system.

Indeed, the Chinese Kapitan was far more efficient than the colonial government in settling conflicts between different dialogue groups and gang fights between secret societies. What made the colonialists feel at ease was the fact that the Chinese community was more concerned about their own problems and interests and would basically not take part in any anti-British political ploys.

As for the secret societies, the colonial government not only did not get rid of them, but allowed them to exert their “localised mini government” functionality in a way that helped the colonial government save on security maintenance cost. Of course, when things went out of hand and caused serious casualties, the colonial police would still step in.

Finally, I want to talk about the day-to-day life of the working class at the bottom of the social hierarchy during the colonial times. This reminds us of the three vice industries of opium, gambling and prostitution in the French concession of Shanghai at more or less the same time.

After Stamford Raffles occupied Singapore in 1819, he set up an opium processing and distribution centre there for distribution to Malaya and other areas. The legalised opium trade fattened the colonial coffers and made large numbers of Chinese migrant workers addicts. Some of the respected community leaders, business tycoons and port operators were actually opium agents who raked in lucrative profits from the business. Before opium was outlawed in 1945, opium dens abounded in towns and villages with substantial Chinese populations.

Gambling was another vice common among the migrant workers seeking excitement and recreation. Coolies who were addicted to opium and gambling not only failed to bring their wives and children here from China but were themselves heavily in debt.

Another major social problem in the Chinese community during the colonial times was disproportionate ratio of male to female population. Statistics showed that the ratio was 5:1 in the federated Malay states of Selangor, Negeri Sembilan, Perak and Pahang. As a consequence, brothels were common in urban areas.

Many brothel owners recruited young girls from the Pearl River Delta of China as prostitutes. The colonial government in Singapore set up a special department to shelter girls rescued from brothels as early as in 1888, which later helped unmarried Chinese men to get their life partners. The department later set up branches across the Malay peninsula.

It is hoped that we can draw some meaningful revelations from the good and not-so-good deeds of early Chinese immigrants and not just to wax lyrical to the more glamorous achievements and obliterate the uglier aspects. Otherwise we will not be able to improve ourselves by drawing invaluable lessons from such unglamorous deeds of our own community.

Many Chinese Malaysians still stick to the old bad habits of gambling and not respecting the speaker delivering a speech in an official ceremony.

To be fair, the quality of early Chinese migrant workers was not any better than the foreign workers we have around us today. While it is true that after six decades of independence, young Chinese Malaysians can now boast vastly improved technological skills and professional knowledge on par with the best in the world, there is still ample room for improvement when it comes to their humanistic qualities.

This I wish to share with you as we usher in the Year of the Rat.

(Wong Tai-Chee has his B.A and M.A degrees in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Paris, and earned his PhD in Human Geography from the Australian National University. After teaching 20 years in Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, he retired in 2013. He then worked as Distinguished Professor for two years at Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, China, and as Dean and Professor at the Southern University College, Johor until the end of 2018. He was Visiting Professor to University of Paris (Sorbonne IV), Visiting Fellow to Pekin University, Tokyo University and University of Western Australia. His main research interests are in urban and economic issues, and more recently on Malaysian politics. Besides his 15 self-authored and edited book volumes, he has written over 100 academic articles and published widely in international journals.)