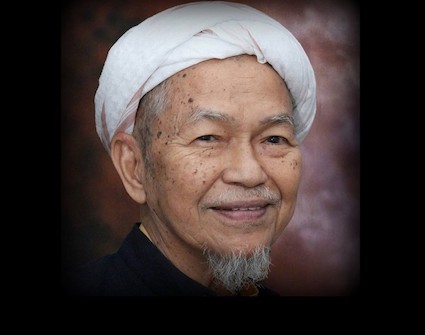

Countering DAP’s fake news on Tok Guru Nik Aziz

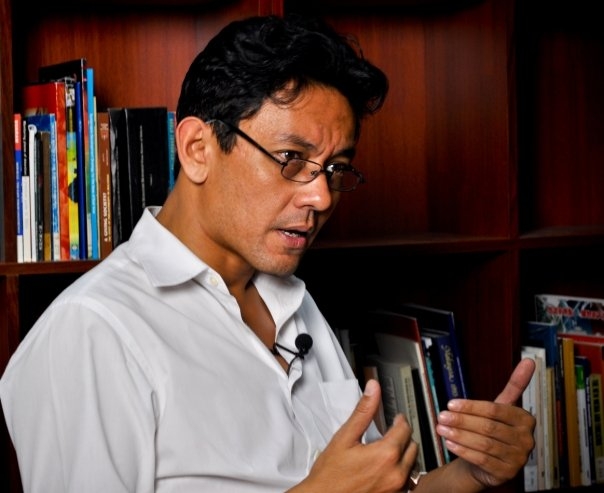

Nik Aziz did not believe in rites and rituals that he regarded as forms of escapism or fatalism, but was more inclined towards an activist-oriented practise of religion where political victory was one of its goals. — Dr Farish A. Noor

NO HOLDS BARRED

Raja Petra Kamarudin

Nik Aziz Nik Mat: The pragmatic reformist who transformed Malaysian politics

Dr Farish A. Noor, The Straits Times, 13 Feb 2015

The passing of Nik Aziz Nik Mat, former Spiritual Leader (Murshid’il Am) of the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party PAS, has left an enormous void in the party and the political landscape of Malaysia. Though his religious educational background was traditional and conservative, he was one of the more pragmatic and realistic leaders of the party, who transformed PAS into what it is today.

Tuan Guru Nik Aziz Nik Mat was one of the most well-known and familiar political-religious leaders in Malaysia, and it would not be an exaggeration to say that he was known throughout the country. Though he was a member of PAS from the 1960s, his popularity began to rise from the 1980s when he, along with a number of religious scholars (Ulama) took over the Pan-Malaysian Islamic Party PAS and deposed its leader Asri Muda, thus initiating the rise of the “Ulama faction” and reorienting the party in the direction of political Islam in keeping with the global rise of Islamism from the 1980s to the late 1990s.

Dr Farish A. Noor: In Pakistan and Egypt, Nik Aziz saw how Muslims had turned Islam into a political force and a tool for mass mobilisation

In Malaysia, he was also known as the Spiritual Leader (Murshid’ul Am) of PAS and the one who was most supportive of the reformist-modernist faction within the party, sometimes referred to as the “Erdogan faction”. The question arises of how and why a traditional and conservative religious scholar such as Mr Nik Aziz could have lent his support to the party’s moderate-reformist wing, who in turn brought the party into the opposition Peoples’ Alliance (Pakatan Rakyat) coalition.

In order to understand the rationale behind Nik Aziz’s thinking, it is important to revisit the man’s past and consider his early religious education abroad, and his experiences in Malaysia and overseas.

Mr Nik Aziz first attended religious schools (madrasah) in Malaysia, but was then sent to India to further his studies. In India, he studied at the Darul Uloom madrasah of Deoband, Uttar Pradesh and it was there that he was first exposed to currents of religio-political thought in the Indian subcontinent. After graduating from Deoband in 1957, he proceeded to Lahore, Pakistan, where he studied Quranic exegesis (Tafsir), and from there proceeded to Egypt where he studied religious jurisprudence (Fiqh) at the well-known al-Azhar university in Cairo.

Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew meeting PAS spiritual leader Nik Aziz on June 14, 2009, in Kota Baru

In India, Pakistan and Egypt, Mr Nik Aziz did not merely study religious subjects but was also exposed to the currents of political Islam of the time: The 1950s and 1960s were the decades where political Islam was on the rise, with prominent Muslim scholar-activists such as Syed Abul Alaa Maudoodi, Sayyid Qutb and Hassan al-Banna becoming better known.

In the course of several interviews that I had conducted with him, Mr Nik Aziz admitted that he was less inclined towards the more poetic and/or spiritual variants of Islam that were found in India: On one occasion he was invited to perform a religious missionary tour with the spiritually inclined Tablighi Jama’at movement in India, but declined on the grounds that he found their practice of Islam ‘world-denying and life-negating’.

He did not believe in rites and rituals that he regarded as forms of escapism or fatalism, but was more inclined towards an activist-oriented practise of religion where political victory was one of its goals.

Nik Aziz moved PAS in the direction of political Islam in keeping with the global rise of Islamism from the 1980s to the late 1990s

Mr Nik Aziz spoke fondly of his time in Egypt, where he professed an admiration for the nationalist project of Gammel Abdel Nasser who had tried to modernise the country and who was seen as one of the leaders of the Pan-Arab nationalist movement. In Pakistan and Egypt, he saw how Muslims had turned Islam into a political force and a tool for mass mobilisation. It was during this period – until his return to Malaysia in 1962 – that Mr Nik Aziz developed his own approach to political Islamism.

Mr Nik Aziz’s educational background was traditional and conservative, and in many of the religious schools he studied at the teaching was based on the Dars-I Nizami curriculum that was introduced in the 11th century. Yet notwithstanding his conservative leanings, his personal experience of living in India, Pakistan and Egypt in the 1950s and early 1960s exposed him to contemporary currents of Muslim activism that later inspired and shaped his own political approach.

After taking over the Islamic party PAS in 1982, he, along with other Islamist-activist leaders like Mr Yusof Rawa (who became PAS’s president then), began the internal transformation of the party and actively courted the membership and support of young Muslim professionals and technocrats into PAS.

It was from the 1980s that PAS became an organisation with strong mobilisation and communications capabilities, as a result of the alliance between the Ulama and professionals that Mr Nik Aziz and Mr Yusof Rawa promoted. Mr Nik Aziz understood the need for a new kind of leadership and membership for the party, that would allow it to mobilise faster and to respond better to both domestic and international challenges.

The younger generation of professionals on the other hand valued the religious knowledge and moral credibility of men like Mr Nik Aziz, as they rejected the capital-driven developmental model they saw in Malaysia and other parts of the post-colonial world. Some analysts and commentators may have misunderstood Mr Nik Aziz’s pragmatic approach to politics for signs of moderation, but it ought to be noted that the guiding principle all along was the desire for state capture and the winning of political power.

Mr Nik Aziz’s passing thus leaves behind an enormous void in the leadership of PAS, and raises questions about where the party might head in the near future. But in recounting his personal history, it is instructive to note that even conservative-traditionalist scholars like him were able to appreciate the importance of networks and pragmatic coalitions as part of political praxis.

Dr Farish A. Noor is Associate Professor at RSIS, NTU; and author of ‘The Malaysian Islamic Party PAS 1951-2013’, Amsterdam University Press, 2014.