Guest Editorial: Addressing ethnic imbalances in the civil service

Of the 1.5 million civil servants, over 90% are Malay. If this trend continues, non-Malays face near-total exclusion from the bureaucracy.

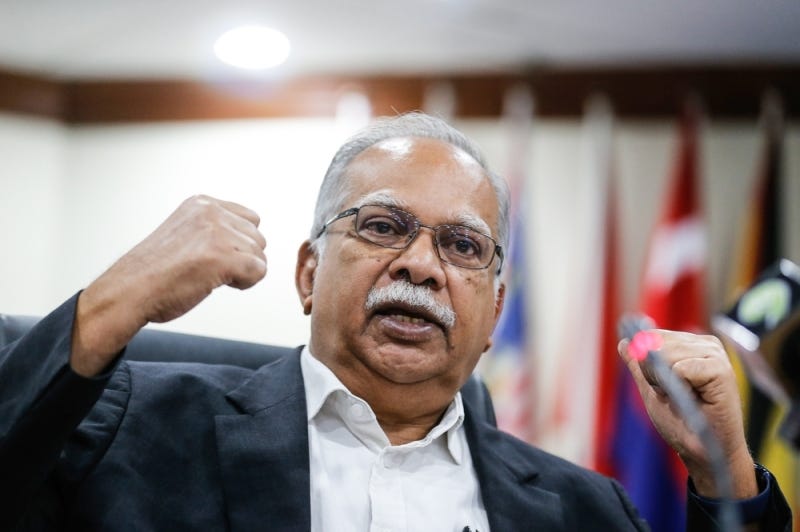

Dr P. Ramasamy

I certainly agree with former judge Hamid Sultan Abu Backer that a return to constitutional principles in the civil service should reflect the multi-racial composition of Malaysia’s population.

Currently, the civil service and other government agencies are predominantly composed of Malays, a trend that began with the New Economic Policy (NEP) in the early 1970s.

While some argue that increasing non-Malay representation could reduce corruption, this issue is not inherently tied to race or religion.

Nevertheless, Hamid’s broader point is valid, as it highlights Malaysia’s systemic challenges where race and religion disproportionately shape public policies.

The Constitution provides safeguards for the special rights of Malays, the status of Malay as the national language, and the position of the rulers.

However, there is no justification for marginalizing non-Malays in employment. What wrong have they committed to warrant such exclusion?

Early last year, while serving in the Penang government, I raised the issue of recruiting more non-Malays into the civil service. To my surprise, the strongest opposition came not just from opposition parties but also from within the government.

Even Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim dismissed my statement as a personal opinion rather than the stance of the DAP leadership.

Subsequently, DAP’s secretary-general hinted at possible disciplinary action against me, and I was ultimately dropped as the DAP candidate for Perai in the 2023 state elections.

This silence from the DAP leadership on the underrepresentation of non-Malays in the civil service suggests that some leaders prioritize political positions and perks over justice and fairness.

The civil service, judiciary, and other government branches are overwhelmingly staffed by Malays.

Of the 1.5 million civil servants, over 90% are Malay. If this trend continues, non-Malays face near-total exclusion from the bureaucracy.

Anwar Ibrahim once championed reforms but has since retreated from these promises. He knows that challenging Malay hegemony in the civil service could jeopardize his hold on power.

Yet, the issue of non-Malay recruitment is not just about reducing corruption; it is about upholding their constitutional right to fair treatment. The Constitution does not justify the marginalization of non-Malays in employment.

The current government lacks the political will to implement progressive changes, betraying the reforms it once promised.

In Penang, balanced employment policies led to increased non-Malay participation in government agencies without displacing Malays.

Meritocracy was not only accepted but embraced by many Malays. Extending this approach nationally could address historical imbalances.

If greater representation reduces corruption, as Hamid argues, it should be pursued. More importantly, it is a matter of constitutional justice and fairness. The wisdom gained from past misdeeds, like the owl of Minerva taking flight at dusk, should guide the government toward righting these historical wrongs.

Malaysians deserve a government that leads them forward, not one that is led by entrenched biases.

Dr P. Ramasamy

Dr P Ramasamy is a former DAP stalwart, academic, former MP and deputy chief minister of Penang. He is also the chairman of a new political party Urimai.